Exclusive

‘Scared Of The Moon’ – The Little Michael Jackson Song That Could

Published

11 years agoon

When Michael Jackson died on the 25th of June 2009, the pop star had unfinished business. And no, I’m not talking about the ill-fated This Is It concert series that awaited him in London. I’m talking about music.

Jackson is well-known for taking longer than most artists to complete and release albums. This is because he was a perfectionist.

“A perfectionist has to take his time,” explains Jackson. “He shapes and he molds and he sculpts that thing until it’s perfect. He can’t let it go before he’s satisfied… You work that thing till it’s just right. When it’s as perfect as you can make it, you put it out there. Really, you’ve got to get it to where it’s just right. That’s the secret.”

For each studio album, Jackson and his collaborators worked on an abundance of material, selecting only the best tracks for the official release.

“As usual [Michael] goes in the studio and he does a lot of stuff, like hundreds of tapes and stuff, you know, and it was great,” recalls Quincy Jones, producer of Jackson’s Off The Wall, Thriller and Bad albums.

“And [Bad] is the one where I asked him to write all the tunes,” continues Jones. “I could see him just growing as an artist and understanding production and all that stuff. Michael had written thirty-three songs, and they were saying, ‘Well okay it’s showdown time! We gotta pick it.’ … You can’t put thirty-three songs on a record. And he’d written some fantastic stuff! Really, really fantastic.”

One of the ‘thirty-three songs’ that Jackson had written during those sessions was “Scared Of The Moon”.

It has been reported that Jackson’s friend, actress Brooke Shields, had told the pop star a story in the early-mid 80s, which inspired the concept of the song. Jackson then worked with songwriter Buz Kohan to bring that concept to fruition.

One of Jackson’s collaborators, Matt Forger, recalls working on the original demo for “Scared Of The Moon” at Westlake Studios.

According to co-writer Kohan, those sessions took place in 1985.

Another of Jackson’s studio collaborators, technical director Brad Sundberg, recalls the simplicity of the original demo.

“They just did the background vocals, the lead vocal and the piano. That was it,” says Sundberg.

With the vocals and piano down on tape, Sundberg recalls that Forger made an innocent mistake:

“Matt [Forger] broke the number one rule that you never break – he gave Michael the master tape. And once you hand anything to Michael Jackson you may as well just chuck it off a pier because you’re never ever going to see it again.”

A short time after recording Jackson’s vocals, Forger received a phone call from an engineer at Evergreen Studios. This is where Forger’s innocent mistake became apparent.

“The engineer was there at Evergreen, calling Matt, saying, ‘Hey I’ve got this Michael Jackson session for ‘Scared Of The Moon’. Michael is here… the string players are here… but we don’t have a tape. Can you run the tape over?’ And Matt’s like, ‘I don’t have the tape… I gave it to Michael!'”

And so they went back and forth, trying to figure out what could be done.

Fortunately, Forger still had a cassette copy of the mixdown of the original demo session. And so he drove the cassette over to Evergreen.

It wasn’t the original multitrack, but it was something.

The engineer at Evergreen then transferred the audio from the cassette onto a new multitrack session, recorded the strings on that same multitrack, and then mixed it all down together.

“From a recording engineer’s standpoint, that’s just breaking every rule in the book,” says Sundberg of their ingenuity. “You cannot take a vocal from a cassette and then put it back onto a multitrack and have it still sound that good.”

“I told Matt that it was pure genius,” adds Sundberg. “It’s just absolutely amazing that it worked because that was the original vocal. It was just a hokey, cute little song that Michael wanted to do. And we did dozens of those. We’d do lots of little snippets where Michael would have an idea and we would do a demo. But how ‘Scared Of The Moon’ came about – technically – shouldn’t have worked, but it does. It was like the little engine that could. It’s the little song that could!”

In the end, “Scared Of The Moon” didn’t make the final cut for Bad, and remained unreleased for almost two decades.

But the track re-surfaced during collaborative sessions for Jackson’s final studio album.

“There are things that just stuck in his mind,” recalls Michael Prince, who served as one of Jackson’s most trusted studio engineers between 1995 and 2009.

“Sometimes he writes new songs, and sometimes he wants to bring up something from the past that he knows is an unpolished gem… I remember we did a little work on ‘Scared Of The Moon’ for the Invincible album.”

Prince continues:

“I remember Steve Porcaro from the band Toto joking, ‘Oh that song again?’ It’s so funny because I’d never heard it before. But that’s Michael’s way of doing things – he always revisited his favourite stuff. He’d say, ‘Why didn’t we put this on our last album? Let’s listen again. Can we make it any better?’ Sometimes it makes it on the album and sometimes it doesn’t.”

As with the Bad album, “Scared Of The Moon” was not selected for Invincible, which was released on October 30, 2001

But then, in November of 2004, Sony Music released The Ultimate Collection – career-spanning box set consisting of both released and unreleased Jackson material. “Scared Of The Moon” was included in that box set.

Listen to “Scared Of The Moon” below – as featured on ‘The Ultimate Collection’:

But despite the fact that the demo had been officially released on The Ultimate Collection, Jackson still wasn’t done with “Scared Of The Moon”.

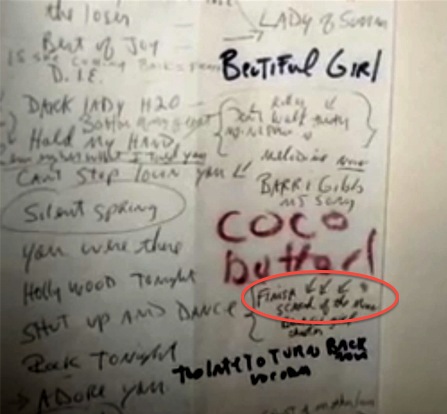

The song, along with many others from different eras of Jackson’s career, was cited in a musical ‘to do’ list the pop star had written in 2009.

The handwritten note, seen below, details the titles of around 30 songs Jackson had hoped to finish.

That particular note was taped to the pop star’s bedroom wall at the time of his death in 2009 – twenty-four years after the “hokey” little demo was first recorded.

Damien Shields is the author of the book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault examining the King of Pop’s creative process, and the producer of the podcast The Genesis of Thriller which takes you inside the recording studio as Jackson and his team create the biggest selling album in music history.

You may like

-

Partnership Between Sony Music and Michael Jackson’s Estate Renewed Amidst Ongoing Fraud Lawsuit

-

XSCAPE: Reviewing the Reviews & Analysing the Clues Regarding the New Michael Jackson Album

-

New Michael Jackson album track list revealed?

-

New Michael Jackson album ‘Xscape’ to be released May 13th – Let’s guess the track list!

-

Jackson 5 Visit to Gloucestershire Inspires Unreleased MJ Track Decades Later

-

Michael Jackson’s Halloween Anthem and the 2009 TV Special That Never Was, But Still Could Be!

28 Comments

Leave a Reply

Cancel reply

Leave a Reply

Cascio Tracks

Supreme Court Judge Grills Sony Lawyer Over ‘Contradictory’ Arguments in Alleged Michael Jackson Fraud

Published

2 years agoon

May 24, 2022

A lawyer defending Sony Music and the Estate of Michael Jackson in a consumer fraud lawsuit has today argued that the billion-dollar corporations should be able to sell forgeries to unwitting consumers – without being held liable for doing so.

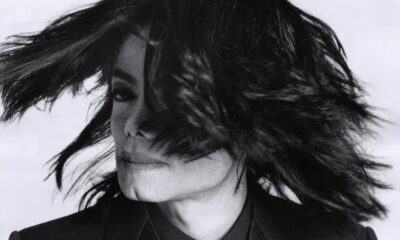

During the California Supreme Court hearing, which was streamed live around the world, Sony attorney Zia Modabber was pulled up for presenting contradictory arguments when attempting to justify the record company’s false attribution of three songs to Jackson on the 2010 Michael album.

The hearing centred around a class action lawsuit filed by Californian consumer Vera Serova – a Michael Jackson fan who purchased the Michael album under the premise that it was a collection of unreleased songs performed by the King of Pop.

In her lawsuit, Serova contends that three of the songs on Michael – “Breaking News,” “Monster” and “Keep Your Head Up” – are forgeries, and that Jackson’s estate and Sony misled her and millions of consumers around the world by falsely representing those forgeries as authentic Jackson material.

Today’s Supreme Court hearing focused specifically on Sony and the Estate’s culpability in the matter.

The corporations argue that the First Amendment (free speech) gives them the constitutional right to lie to consumers without remedy, and that they should be removed from the lawsuit because of this.

In fact, Sony and the Estate have been petitioning to be removed from this case for 6 years, alleging that plaintiff Serova strategically filed her lawsuit to prevent the record company from exercising their First Amendment right to participate in the public dialogue regarding the authenticity of the songs.

The dialogue in question is the wording on the reverse side of the album cover, which stipulates that the vocals on the album were “performed by Michael Jackson” (see below).

In a 2016 hearing regarding this matter, attorney Zia Modabber argued on behalf of Sony and the Estate that if anyone were to be held liable for the fraud it should be the original producers of the songs – Eddie Cascio and James Porte – because they provided them under the false pretence that they were authentic.

Today, in front of seven Supreme Court Justices, Mr. Modabber made the same argument on behalf of Sony and the Estate.

In what was a rollercoaster hearing, Modabber told the court that Sony and the Estate were “100%” certain that the vocals on the songs in question were authentic based on an investigation conducted by former Estate attorney Howard Weitzman in November 2010.

A few minutes later, in a complete about-face, Modabber claimed that neither Sony nor the Estate were in a position to know who sang the vocals – a backflip which Justice Groban took issue with:

“How can it be both? Why is Sony saying with 100% certainty that Michael is the singer if you weren’t certain? Which is essentially what I hear you saying now.”

Mr. Modabber also made a number of arguments throughout his 30-minute presentation which seemed only to benefit plaintiff Serova’s side.

At one point, Modabber explained the identity of the artist is what gives art its meaning and value. In other words, if Michael Jackson wasn’t singing on the songs in question, they’d be irrelevant and worthless:

“The identity of the artist is part and parcel of the art. It imparts meaning to the art.”

The attorney, on behalf of Sony and the Estate, went on to give an example:

“There’s a song that Michael wrote called Leave Me Alone, and it’s about being persecuted by the press. When Michael Jackson sings that song – because it’s Michael Jackson singing it – it gives a certain meaning to that song. If I sang that song – nobody cares about me – it doesn’t have the same meaning as if Michael Jackson sings that song. And that’s why authors and the source of the art are part of – and intimately connected to – the art itself… It undeniably adds to the meaning of the art.”

Lawyer for Sony and the MJ Estate, Zia Modabber: “The identity of the artist is part and parcel of the art. It imparts meaning to the art.”

— Damien Shields (@DamienShields) May 25, 2022

He explains it was necessary for Sony to attribute 3 fake songs to Jackson, because without that false attribution they’d be meaningless. pic.twitter.com/6Mg0Y0vHES

Without Michael Jackson’s name on the songs in question, they couldn’t commercially exploit them.

Therefore, according to Sony’s logic, the company had no choice other than to falsely attribute the authorship to Jackson in order to give them meaning and value in the eyes of consumers.

In what can only be described and an own goal, Modabber continued by asserting that the consumers of art want to know who the artist is, and that he cannot think of a scenario in which the identity of the artist doesn’t matter:

“Imagine art, out in the world, with no attribution of authorship. Imagine you just didn’t know who it came from or what the source was. It’s not the same. There is a character and a quality and an impact and a curiosity by those who consume the art about where it came from and what the source was. It adds meaning to it. We want to know who it is. We want to know where it came from. We want to know what inspired it. And part of that is the identity of the artist. And so I can’t think of a situation where the identity of the artist doesn’t matter.”

“I can’t think of a situation where the identity of the artist doesn’t matter.”

— Damien Shields (@DamienShields) May 25, 2022

Sony lawyer Zia Modabber says art is “not the same” to consumers unless they know who the artist is, because the attribution of authorship to the artist gives the art “character, quality and impact.” pic.twitter.com/TPxKXr6Mci

More to come when the California Supreme Court hands down their ruling on this matter.

For those of you who are interested, a podcast series detailing my investigation of this case, called Faking Michael, is currently in production. Subscribe to Faking Michael on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or YouTube to be notified when episodes are released.

Damien Shields is the author of the book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault examining the King of Pop’s creative process, and the producer of the podcast The Genesis of Thriller which takes you inside the recording studio as Jackson and his team create the biggest selling album in music history.

Creative Process

Invincible, ‘Xscape’ and Michael Jackson’s Quest for Greatness

Published

3 years agoon

October 30, 2021

Below is a chapter from my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault, revised for this article. The full book is available via Amazon and iBooks.

In order to fully appreciate the origins and evolution of “Xscape” – an outtake recorded for Michael Jackson’s Invincible album – it’s important to first understand Jackson’s relationship with its co-writers.

The journey begins in early 1999, when in-demand producer Rodney ‘Darkchild’ Jerkins received a phone call from renowned songwriter Carole Bayer Sager.

Bayer Sager’s working relationship with Michael Jackson dates back to the late 1970s, when she and producer David Foster co-wrote “It’s The Falling In Love” – a duet recorded by Jackson and R&B star Patti Austin, which was released on Jackson’s Off The Wall album in 1979.

Two decades later, Jackson and Bayer Sager were again working together.

During her 1999 phone call with Jerkins, Bayer Sager explained that she and Jackson were writing songs for Jackson’s next studio album at her home in Los Angeles, and that they wanted Jerkins to join them.

“He was this guy who went around Hollywood, and around the industry, saying his dream was to work with me,” explains Jackson.

“I was at Carol Bayer Sager’s house, who is this great songwriter who has won several Academy Awards for her songwriting, and she said: ‘There’s a guy you should work with… His name is Rodney Jerkins. He’s been crying to me, begging to meet you. Why don’t you pick up the phone and say hi to him?’”

Jerkins recalls that in the end, Bayer Sager made the call:

“Carole called me and said that she was gonna have a writing session at her house with Michael Jackson and she wanted me to do a track. I was like, are you serious?”

And so the producer immediately booked a flight from New Jersey to Los Angeles and headed straight to Bayer Sager’s home.

“I went over there and it was just an amazing experience. I was in awe,” recalls Jerkins.

“I’ve always heard people that worked with him say, ‘When you meet Michael, it’s crazy!’ But I’m the type of guy who’s like nah, I’ma be okay, I’ma be cool. It’s just another artist. And then once I got there, and was in his presence, I was like whoa, this is crazy!”

Jerkins explains that not seeing Jackson at the industry events or private parties added to his untouchable mystique, but that once the pair got in the studio together a friendship was born:

“Once I got in the studio, and once he felt comfortable with me, and I felt comfortable with him, it was like the best thing ever. And we just built a really solid friendship throughout the years. And we stayed working and stayed in contact and he was just a great guy.”

But the collaborative relationship between Jackson and Jerkins almost didn’t come to fruition.

Jackson recalls that when he met Jerkins at Carole Bayer Sager’s home in early 1999, Jerkins asked Jackson if he could have two weeks to work on a collection of ideas to present to him:

“He came over that day and he said, ‘Please, my dream is to work with you. Will you give me two weeks and I’ll see what I can come up with.”

Two weeks later, Jackson met with Jerkins for a second time, and Jerkins played him the collection of tracks he’d come up with.

“The day that Rodney met with Michael, he played him all these records,” recalls Cory Rooney – a songwriter and producer who was working as the Senior Vice President of Sony Music at the time.

“Michael was like, ‘It’s not that the guy’s not talented, but everything he plays me sounds typical. Like Brandy and Monica,’ whom Rodney had worked with previously.”

According to Rooney, the pop star didn’t want to fit in with the current industry sound of the time. Jackson wanted to pioneer his own new sound.

“And Michael just said, ‘I don’t wanna sound like Brandy and Monica. I need a new Michael sound. Big energy.’ And this is after Rodney played him twenty records.”

At this point, Jackson wasn’t sure whether Jerkins was the right man for the job.

“So Michael came back to me and said, ‘I don’t know if he’s the guy.’ And I was so sure that Rodney Jerkins was the most rhythmic, hard-hitting sound out there in terms of producers – other than Teddy Riley who was that at one point for Michael – I just said this is the guy. Rodney’s the guy.”

Rooney’s belief that Jerkins could essentially be Jackson’s ‘new Teddy Riley’ was no coincidence given that Jerkins grew up idolising Riley’s production style.

“Teddy Riley was the producer that changed my life,” recalls Jerkins.

“I remember being eleven years old and trying to emulate Teddy Riley. He was everything. He was everything to my career. Then having the opportunity to meet him at fourteen years old, and to play my music for him, and him telling me that I was good enough to make it was the inspiration and extra encouragement that I needed to know that this was real; that I wasn’t just some kid in a basement trying to make beats, but actually someone who could have a career.”

Riley went on to mentor Jerkins for years, and was reportedly responsible for Jerkins’ first encounter with the King of Pop at age sixteen, five years before he got the chance to work with Jackson.

And so despite his reservations, based on Rooney’s strong recommendation that Jerkins could deliver, Jackson remained open-minded about working with the producer.

“So Michael said, ‘I’ll tell you what, Cory. Do you think Rodney would mind me telling him that he kind of needs to reinvent himself for me?’” recalls Rooney.

“I said of course Rodney wouldn’t mind. I said I’ll have the conversation with Rodney, then you can have the conversation with Rodney. So I went, on my own, and talked to Rodney and told him what Michael felt.”

Following Rooney’s heart-to-heart conversation with Jerkins, the producer met again with Jackson. Rooney recalls:

“At that point, Michael set up the meeting and said to Rodney, ‘I want you to go to your studio and I want you to take every instrument, and every sound that you use, and throw it away. And I want you to come up with some new sounds. Even if it means you’ve gotta bang on tables and hit bottles together and make new sounds. Do whatever you’ve gotta do to come up with new sounds and use those new sounds to create rhythmic big energy for me.’ Michael put the challenge to Rodney, and Rodney accepted.”

“I remember having the guys go back in and create more innovative sounds,” recalls Jackson.

“A lot of the sounds aren’t sounds from keyboards. We go out and make our own sounds. We hit on things, we beat on things. They are pretty much programmed into the machines. So nobody can duplicate what we do. We make them with our own hands, we find things and we create things. And that’s the most important thing, to be a pioneer. To be an innovator.”

“He changed my whole perception of what creativity in a song was about,” explains Jerkins.

“I used to think making a song was about just sitting at the piano and writing progressions and melodies. I’ll never forget this crazy story. Michael called me and says, ‘Why can’t we create new sounds?’ I said, what do you mean? He was like, ‘Someone created the drum, right? Someone created a piano. Why can’t we create the next instrument?’ Now you gotta think about this. This is a guy – forty years old – who has literally done everything that you can think of, but is still hungry enough to say ‘I wanna create an instrument.’ It’s crazy.”

Jerkins recalls that following Jackson’s orders, he went out and began sampling sounds to use in their records:

“I went to a local junkyard and I started gathering trash cans and different things, and I began to hit on them to try to find sounds. Michael told me to. Michael said, ‘Go out in the field.’ That was his term. He used to say, ‘Go out in the field and get sounds. Don’t do it like everybody else and go to a store and buy equipment. Go out in the field and get sounds.’ So I went out in the field and got sounds.”

After building a library of junkyard sounds to use in the tracks Jerkins, his brother Fred, and songwriter LaShawn Daniels – who form the Darkchild production team – started the writing process.

But they were unsure of exactly how to write for Jackson, especially since he hadn’t been thrilled with the first batch of songs.

Cory Rooney recalls:

“Rodney called me and said, ‘Cory, we’re still confused. We don’t know what to write about. We don’t know what to do.”

At the time, Rooney had just written a song for Jackson called “She Was Loving Me,” which Jackson had flown to New York to record with Rooney at the Hit Factory.

Upon his return to LA, Rooney says that Jackson played the track for Jerkins and his team.

“Rodney said, ‘Cory… he loves your song. All he keeps playing for us is your song. What is it about your song that you think he loves? So I told him I got a little tip from Carole Bayer Sager. She told me that Michael is a storyteller. She said Michael loves to tell stories in his music. If you listen to Billie Jean, it’s a story. If you listen to Thriller, it’s a story. If you listen to Beat It, it’s a story. He loves to tell a tale.”

The Darkchild production team began working on music for Jackson at an LA studio called Record One, where other Jackson collaborators including Brad Buxer, Michael Prince and Dr. Freeze were already working on their own ideas for the pop star.

“Rodney was running his sessions like twenty-four hours per day,” remembers Prince.

“They even brought beds in to sleep on. When Rodney would get tired, he would go and lay down and Fred would come in and work on lyrics. When Fred would get tired, he’d go and wake up LaShawn, who would come in and work on some things.”

“Michael would call the studio at two or three o’clock in the morning to just check in and see what we were doing,” recalls Rodney’s brother, Fred Jerkins III.

“He was constantly motivating us to think beyond the scope of our normal imagination with these songs. It was incredible.”

“I used to sleep in the studio,” recalls Rodney.

“At every studio that I worked, I would make sure that they had a pull-out bed or something brought in for me because I would stay there for weeks at a time.”

Recording engineer Michael Prince recalls that the Darkchild production team worked so hard that the studio engineers couldn’t keep up:

“At some point, I remember the engineers coming to me and saying, ‘We can’t keep doing this. This is killing us!’ And I was like, just tell them. They’re people too! But they hung in there as long as they could.”

Producer Rodney Jerkins says that his work ethic was inspired by Jackson.

“He told me that if I was willing to really work hard, that we could make some magic together, and that’s what I did… I went in the studio and just really locked in and started creating nonstop every day.”

“We were in the studio for maybe a month before Mike came in, and we had all our ideas down. We had our melodies down, everything,” recalls Darkchild songwriter LaShawn Daniels.

“So when Mike finally came in, it was like the President coming in. The place was swept. Security came in, and it was going crazy.”

But it was Jackson’s knowledge of each member of the Darkchild production team that impressed Daniels the most:

“He came into the room and – surprisingly – he knew who each one of us was and what we did in respect to the project! Mike was so in tune with music as a whole that the stuff he told us still blows my mind.”

In a further attempt to point the Darkchild production team in the right direction when working on songs for Jackson, Cory Rooney suggested that they start simple:

“I told Rodney, let’s start with the rhythm. I said if you’re confused on the rhythm, just start with that four on the floor beat, because that never goes wrong. And just create your rhythms to counter the four on the floor.

With that advice in mind, the Jerkins brothers and LaShawn Daniels wrote a song that they believed was a hit.

“And that became the track for You Rock My World. And the rest is history because LaShawn Daniels and everybody dug in and wrote a story to it.”

Rodney Jerkins explains how “You Rock My World” came to be:

“Rock My World came about because I’m a fan of old Michael – like Off The Wall, Thriller, and The Jackson Five.”

Jerkins recalls that while Jackson was demanding new sounds, he felt it was also important to write songs that retained Jackson’s classic sound:

“Michael was like, ‘I want you to go outside and to take a bat and smash it against the side of a car and sample it.’ And I was doing it! He had me at junkyards with DAT recorders. And I was like, that’s all good, I’ll give you that, but you have to do this over here. And Rock My World was actually the first song that we wrote for Michael.”

By the time the demo to “You Rock My World” was ready for Jackson to hear, studio sessions had been shifted from Record One in Los Angeles to the Hit Factory and Sony Studios in New York City.

Rooney recalls that at that time, the Darkchild production team called him and invited him to come down to the studio to take a listen:

“They called me at the Hit Factory and said, ‘Cory, you’ve gotta come over. We think we’ve got it.’ When I walked in and they played me Rock My World, I almost passed out! I thought it was so amazing that I almost passed out. I was really, really blown away.”

Rooney recalls that he took the song to Jackson, so that he could hear the track:

“When I first played it for him he, asked me: ‘Do you love it?’ And I said yeah, yeah, I love it! And he said, ‘Well, I know you wouldn’t have come over here and played it for me if you didn’t like it, but do you love it?’ And I looked him right in his eyes and said Michael, I love it. I love this record. And he said, ‘Okay. I’ve got to be honest with you. I do like it. I don’t know if I love it yet, but I like it, and I’m going to just keep on living with it.’”

Rooney continues:

“If Michael is just a little bit interested in a song, you’re never gonna get him in the studio to record it. And so he lived with it, and showed up at the Sony studios in New York about a week later, with Rodney, and he kind of ran through the record.”

Darkchild songwriter LaShawn Daniels – who was an integral part of writing “You Rock My World” – remembers the moment Jackson came to the studio to work on the track.

“He had Rodney just play the track, and he said, ‘Who’s the guy doing the melodies?’ And it was me!”

Daniels continues:

“So I came into the room and Michael is standing there – freakin’ Michael Jackson! – and Mike comes up to me and says, ‘Rodney, play the track.’ And Rodney says, ‘Sure.’ Then Michael says to me, ‘Can you sing the melodies into my ear?’ And I’m like, are you serious? He’s like, ‘Just sing it in my ear.’ So I go right next to him, and I pull towards his ear, and I start singing.”

Daniels recalls that Jackson stopped him, and suggested they make minor change.

“He puts his hand on my shoulder and says, ‘No. Let’s change this part.’ And I’m like, oh, my god! When he asked me to do that, I was done. I couldn’t even continue, and I had to stop. I said, Mike, listen, I appreciate you being so cool, but you can’t be this cool with me. I don’t even know what to do right now. And I can’t concentrate on the melodies because I’m singing to Michael Jackson! And he burst out laughing and just made us comfortable.”

Former Sony executive Cory Rooney recalls that from there, Jackson had Jerkins repeat the track a few more times before recording a scratch vocal to see how he felt about it with his own voice on it.

“He played with it a little bit and sang the first few lines. And then he played it back, listened to it with his voice on it, and said, ‘Okay, now I love it! So let’s go to the top, and I’m gonna kill this record.’ And everybody was so relieved.”

Rooney recalls that Jackson loved the background vocals LaShawn Daniels had recorded, and he wanted to include them on the Darkchild tracks – something that Jackson had also done with songs he recorded with producer Dr. Freeze a year prior.

“Michael said: ‘Man, you’re killing it. I love it! Sounds great.’ He loved LaShawn Daniels’ background vocals so much that he left them on You Rock My World and other songs they worked on together. Michael did the main notes but he left LaShawn in the background.”

Once “You Rock My World” was completed, Jackson challenged his newfound collaborative team to create even greater material.

“Those times with Michael… he taught me to challenge myself,” recalls Daniels.

“When we came up with the Rock My World melodies and everything, it felt great. We knew that was the record. But he came back and he said, ‘Challenge yourself. I’m not saying that this is not it, but can you beat it? If you can beat it, you’ve only touched greatness even more!’”

To guarantee that their focus would be on his project – and his project only – Jackson reportedly paid Rodney Jerkins the Darkchild production team not to work with anyone but him.

“He told me he wanted me to camp out and work on his album,” recalls Jerkins.

“I was slated to do about seven or eight artists… and Michael said, ‘No, no, no. You have to really focus on my project. I need you to really focus on this.’ And I was like yeah, but I got bills to pay. And he said, ‘I’ll take care of those. Tell me what they’re gonna pay you and how many songs and I’ll take care of it.’ So I ended up not working with all those different artists and just focusing on Michael.”

As production on the album progressed, the Darkchild team returned to New Jersey to continue working on unique sounds for Jackson, crafting rhythmic tracks from their library of sampled sounds – including sounds from those initial junkyard recordings.

“The process of working with Michael Jackson was so intense because he pushed me to the limit creatively,” explains Jerkins.

“He loves to create in the same kind of way that I like to create,” Jackson says of Jerkins.

“I pushed Rodney. And pushed, and pushed, and pushed, and pushed him to create. To innovate more. To pioneer more. He’s a real musician. He’s a real musician and he’s very dedicated and he’s really loyal. He has perseverance. I don’t think I’ve seen perseverance like his in anyone. Because you can push him and push him and he doesn’t get angry.”

“Michael would call me at four o’clock in the morning and say, ‘Play me what you got,’” remembers Jerkins.

“I’m like, um, I’m about to go to sleep. But that’s how he was. He was so into the creative zone. On most of the stuff I did with him, the snares were made out of junkyard materials.”

One of the songs that sprouted from the 1999 Darkchild sessions in New Jersey sessions was “Xscape” – originally penned as “Escape” per an early ASCAP Repertory listing.

“Xscape was a record that I actually wrote the hook for myself,” recalls Fred Jerkins III, adding that he even sang the very first demo of the track:

“I don’t do any singing on songs at all. But on that one I actually had to sing the demo first, before it went to LaShawn to do the final demo version. So I actually had to get in the booth and sing it, and then the rest of the song was built around the hook idea.”

An early demo of “Xscape” was first shown to Jackson during a phone call with Rodney Jerkins.

When Jackson heard what they’d come up with, according to Jerkins, he went crazy:

“He was like, ‘That’s what I’m talking about! That’s what I’m talking about!’ It made him want to dance… Michael, he just loved to dance and would always tell me, ‘Make it funky.’ So musically I kept the promise and he kept the promise melodically, and we made up-tempo songs that made you wanna dance.”

As with Cory Rooney’s “She Was Loving Me” a few months earlier, Jackson was so in love with “Xscape” that he wanted to recording it immediately.

Instead of travelling to New Jersey – where the Darkchild production team was working – Rodney Jerkins had Jackson use a new recording technique designed by EDnet that allows engineers to capture high-quality audio through a phone line.

And so Jackson sang the background vocals – usually the first part of a song Jackson would record – down the phone while Rodney recorded them.

“From that point we would go in and do the complete demo version,” recalls Rodney’s brother, Fred Jerkins III.

“LaShawn was the one who would demo on all of the songs for Michael, and he did a good job of trying to imitate him. We would try and provide the best feel for Michael about how the song should be.”

When the demo was ready, producer Rodney Jerkins collaborated with Jackson on the lyrics before recording the lead vocals. Co-writer of the track, LaShawn Daniels, explains:

“What we did with Michael – because he was a great songwriter – is we had the tracks and we put the rhythm of the melodies down so when he came in he could hear the basic idea of what we wanted to do, but allow him to be a part of the creative process of lyrics and all that type of stuff.”

Allowing the hook to lead the way, the track’s lyrics became a defensive musical exposé in line with previously-released tracks like “Leave Me Alone” and “Scream” – about how the pop star’s privacy is rarely respected, and how details of his private life are often twisted or fabricated when reported on in the media.

As with all of his music, Jackson was intimately involved with every nuance of “Xscape”.

Over the course of two years, Jackson and Jerkins continued to tinker with the track, adding new sounds and samples while bringing it closer and closer to completion.

“I tell them to develop it, because I’ve got to go on to the next song, or the next thing,” explains Jackson of his collaborative relationship with producers and songwriters.

“They’ll come up with something, working with my] ideas, and they’ll get back to me, and I’ll tell them whether I like it or not. I have done that with pretty much everything that I have done. I am usually there for the concept. I usually cowrite all the pieces that I do.”

“That was our process,” explains Rodney Jerkins.

“That’s the way we worked. We just kept at it until it was ready. We just worked on ideas, added this and that to the mix. Michael was like, ‘Dig deeper! Where’s the sound that’s gonna make you want to listen to it over and over again?’”

Engineer Brian Vibberts recalls working with Jerkins on “Xscape” at Sony Music Studio in New York City during the summer of 1999.

Vibberts, who also worked on Jackson’s HIStory album in 1995 and music for his Ghosts film in 1996, claims that Jackson was physically present at the studio far less during the Invincible sessions when compared to previous projects.

“Rodney would send the song to Michael, then talk to him on the phone. Michael would give him input on the song and request the changes that he wanted made. Then we would do those changes.”

One of the changes that was made to the original Darkchild demo was the addition of a cinematic spoken intro.

“He called them vignettes,” says Rodney Jerkins. “I call them interludes.”

“It was a really fun process, working on that project,” adds Rodney’s brother, Fred.

“We would actually sit in the studio in LA and act out the whole Xscape concept, the intro, just acting crazy and making video footage and all that kind of stuff. Almost like our video concept of the song.”

Another interesting addition to “Xscape,” which Jackson brought to the table, is the Edward G. Robinson line from the 1931 film Little Caesar: “You want me? You’re going to have to come and get me!”

Fifteen years prior, the same line was lifted from the film and sampled in an unreleased version of Jackson’s demo for a song called “Al Capone,” as outlined in the Blue Gangsta chapter of my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault.

In “Xscape,” however, Jackson himself speaks the famous line, shortening it to: “Want me? Come and get me!” ‘

Of the decision to include the Little Caesar line, producer Rodney Jerkins says: “It was MJ’s idea.”

By the middle of the year 2000, the Jackson’s new album seemed to be nearing completion.

Since he started working on it in 1998, Jackson had recorded more than a dozen tracks including “She Was Loving Me,” “You Rock My World,” “Xscape” and “We’ve Had Enough” – the latter of which spawned from the early 1999 writing session Jerkins attended at Carole Bayer Sager’s home in LA.

With enough tracks in the bag to finish the album, the mixing process began.

To assist Jackson’s team with mixing the album, producer Rodney Jerkins brought an engineer named Stuart Brawley on board.

“Michael’s longtime engineer of many years, Bruce Swedien, was looking for someone to come on board to help mix what we all thought at that time was a complete record,” recalls Brawley.

“It was supposed to be a month-long mixing process in Los Angeles and I just jumped at the opportunity to be able to work with both Michael and Bruce.”

But what was supposed to be just one month of mixing ended up being much more.

“It turned into a thirteen-month project because as we were mixing the record that we thought was going to become Invincible, Michael decided, in the mixing process, that he wanted to start writing all new songs,” recalls Brawley.

“He was like, ‘Let’s start from scratch… I think we can beat everything we did,’” recalls Rodney Jerkins of Jackson’s decision to start afresh by writing new songs.

“That was his perfectionist side. I was like man, we have been working for a year, are we going to scrap everything? But it showed how hard he goes.”

“It just turned into an amazing year of watching him create music,” recalls engineer Stuart Brawley. “We ended up with a completely different record at the end of it.”

While some of the early material – including “You Rock My World” – would ultimately make the cut, the majority of what became the Invincible album was recorded between 2000 and 2001.

During this period, the Jerkins brothers and LaShawn Daniels continued working on new songs, while Jackson’s longtime producer Teddy Riley also joined the team.

At the time, Riley was working out of a studio that was built inside a bus.

Upon joining the project, Riley would park his bus outside whichever studio Jackson was working in, and and the pop star would bounce back and forth between Riley and Rodney Jerkins.

Meanwhile, arranger Brad Buxer and engineer Michael Prince worked out of makeshift studios set up in local hotel rooms.

Towards the end of the project, Riley moved his sessions to Virginia – where he had a recording studio – to finish the tracks he was working on.

Recording engineer Stuart Brawley – who was instrumental in recording and editing some of the newer songs, like “Threatened” – recalls what it was like to work with Jackson:

“It was amazing just to have him on the other side of the glass when we were recording his vocals. It literally was that ‘pinch me’ moment, and I don’t get those. He was just one of a kind. There was no one else like him.”

“Being in the studio and just having the a cappella of Michael’s vocals and listening to them, you start to really understand how great he really was,” explains Rodney Jerkins of Jackson’s performance on “Xscape.”

“The way he crafted his backgrounds, the approach of his lead vocals, and how passionate he was. You can hear it. You can hear his foot [stomping] in the booth when he’s singing, and his fingers snapping.”

During the second phase of the Invincible album’s production – between 2000 and 2001 – Jackson and Jerkins continued to work on “Xscape.”

“Wait until the world hears Xscape,” Jerkins recalls Jackson saying to him.

“MJ loved everything about it. The energy, the lyrics. It’s kind of a prophetic song. Listen to the bridge. MJ says, ‘When I go, this problem world won’t bother me no more.’ It’s powerful.”

“The thing about Michael is he will work on a song for years,” adds Jerkins.

“We never stopped working on the song Xscape.”

“A perfectionist has to take his time,” explains Jackson.

“He shapes and he molds and he sculpts that thing until it’s perfect. He can’t let it go before he’s satisfied; he can’t… If it’s not right, you throw it away and you do it over. You work that thing till it’s just right. When it’s as perfect as you can make it, you put it out there. Really, you’ve got to get it to where it’s just right; that’s the secret. That’s the difference between a number thirty record and a number one record that stays at number one for weeks. It’s got to be good. If it is, it stays up there and the whole world wonders when it’s going to come down.”

Jackson continues:

“I’ve had musicians who really get angry with me because I’ll make them do something literally several hundred to a thousand times till it’s what I want it to be,” says Jackson. “But then afterwards, they call me back on the phone and they’ll apologise and say, ‘You were absolutely right. I’ve never played better. I’ve [never] done better work. I outdid myself.’ And I say, ‘That’s the way it should be, because you’ve immortalised yourself. This is here forever. It’s a time capsule.’ It’s like Michelangelo’s work. It’s like the Sistine Chapel. It’s here forever. Everything we do should be that way.”

After three years of work, the Invincible album was released on October 30, 2001.

The album contained 16 songs. But to the surprise of some who worked on the project, “Xscape” was not one of them.

“There’s stuff we didn’t put on the album that I wish was on the album,” explains Jerkins, whose unreleased material includes “Get Your Weight Off Me” and “We’ve Had Enough” – the latter of which was later released by Sony on a box set called The Ultimate Collection in 2004.

A number of tracks Jackson recorded with Brad Buxer and Michael Prince also missed the cut, including “The Way You Love Me,” which was also released on The Ultimate Collection box set.

Several tracks Jackson worked on with producer Teddy Riley did make the cut. But one, called “Shout,” did not.

“Shout” was slated to be on the album, but was replaced at the last minute by a track Jacksons’s manager, John McClain, brought brought to the table called “You Are My Life” – co-written by McClain with Kenneth ‘Babyface’ Edmonds and Carole Bayer Sager.

“I really want people to hear some of the stuff we did together which never made the cut,” laments producer Rodney Jerkins.

“There’s a whole lot of stuff just as good – maybe better [than what made the album]. People have got to hear it.”

Despite it not being included, Jackson continued working on “Xscape” with Jerkins.

The producer explains that selecting the tracks for an album isn’t always about which tracks are best in isolation, but which tracks fit together to create a cohesive and organic flow:

“Michael is like no other. He records hundreds… really, hundreds of songs for an album. So what we did [was] we cut it down to 35 of the best tracks and picked from there. [It’s] not always about picking the hottest tracks. It’s got to have flow. So there’s a good album’s worth of [unreleased] material that could blow your mind. I really hope this stuff comes out because it’s some of his best.”

Engineer Michael Prince recalls a conversation he had with fellow engineer Stuart Brawley about the unreleased track “Xscape” after the Invincible album had been released.

“I was talking to Stuart Brawley on the phone… And I said to Stuart, this song is awesome! And he goes, ‘I know. It’s an amazing song. I really, really wish they would have put that on the album and took something else off. I told Rodney, I told Michael, but they’re not putting it on the album.’ And after I heard it I felt the same way. I really like the song Xscape.”

“I had a conversation with MJ in 2008, and I asked him if he was a fan of the British act Scritti Politti,” adds Prince.

“He said he was. I asked him that because the original version of Xscape has some of the same type of short staccato sounds and sampled percussive sounds that Scritti Politti use in their music. They also used very inventive sequencing, as Michael and Rodney Jerkins did on Xscape.”

“When we originally did Xscape, Mike felt it was some of his best new music,” recalls Rodney Jerkins.

“So I asked him, Michael, how come Xscape is not going on Invincible? And Michael was like, ‘Nah… I don’t want it on this project. I want it on the next project.’ Michael was very clear in telling me that one day that song has to come out… It was one of his favourite songs… It was one of those songs where he specifically said to me, ‘It has to see the light of day one day’… He felt compelled to let the fans hear it. What does it do for a song that Michael really loved to just sit in the vault somewhere?”

And eventually Jackson’s fans did hear it – but not in the way he or Jerkins had hoped.

In late 2002, “Xscape” leaked online.

“The reality is that you get upset when something gets out there that’s not supposed to be out there,” explains Fred Jerkins of his feelings about the leak.

“You want it to come out the way it should, and to give it the best possible chance of doing what it needs to do. But at the same time, as a fan – if you step aside from the songwriter side – you’re excited that you have something out there. And you watch other people get excited.”

Reflecting on their work with Jackson on “Xscape” – and the Invincible project as a whole – the thing that sticks with Darkchild teammates Rodney Jerkins and LaShawn Daniels more than anything is his desire to be great.

“Michael embodied greatness in everything that he did,” says Jerkins.

“Not just as an artist, but as a humanitarian and as a person. That was his life. He was all about being great and he preached it all the time.”

Since he was a teenager, Jackson’s artistic philosophy has been to ‘study the greats and become greater,’ and for the duration of his four-decade career, that pursuit of greatness never faded.

“Michael would be in the lounge watching footage on Jackie Wilson, James Brown and Charlie Chaplin,” recalls Jerkins.

“And I walk in and I say, what are you doing? And he said, ‘I’m studying.’ Now mind you, he had all of the Grammys, millions and millions of albums sold, and I said why are you studying? And he said, ‘You never stop studying the greats.’ And he was about 40 years old when we were working together. That was a serious, serious lesson for me as an up-and-coming person to hear him say that, and to witness that.”

“Even if you’re sweeping floors or painting ceilings,” explains Jackson, “do it better than anybody in the world. No matter what it is that you do, be the best at it.”

In 2013, President of Epic Records at the time, L.A. Reid, recruited several of A-list producers to reimagine 8 unreleased songs from Jackson’s vault.

Rodney Jerkins was one of those producers.

Initially Jerkins was hesitant to be involved, and resisted producing his remix until he had heard the material other producers were contributing.

“I care,” explains Jerkins.

“Michael was a friend of mine. I had a good relationship with him. He knew my family and I knew his family. So I would tell L.A. I’m not doing a song until I hear the rest of the album… I wanted to make sure that everything stood up to what Michael would have wanted. That was important to me.”

Eventually, when he felt the project was worthy of Jackson’s dedication to greatness, Jerkins agreed to participate.

The song he produced was “Xscape”.

On May 9, 2014, five years after Jackson’s death, “Xscape” was officially released by Epic Records on an album of the same name.

“It’s about being great. It’s about being groundbreaking. If it can’t be great, we shouldn’t be doing it,” explains Epic boss L.A. Reid of his philosophy when putting the album together, adding:

“Michael Jackson tapped us on the shoulder and said would you just do me one small favour and remind people that I’m the greatest.”

Damien Shields is the author of the book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault examining the King of Pop’s creative process, and the producer of the podcast The Genesis of Thriller which takes you inside the recording studio as Jackson and his team create the biggest selling album in music history.

Creative Process

‘Blue Gangsta’ and Michael Jackson’s Fascination with America’s 20th Century Underbelly

Published

3 years agoon

October 29, 2021

Below is a chapter from my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault, revised for this article. The full book is available via Amazon and iBooks.

Released in 1987 as part of the Bad album, “Smooth Criminal” is the culmination of years of Michael Jackson toying with the idea of doing a song based on early 20th-century organised crime in America.

The King of Pop’s ongoing fascination with the mobsters and gangsters of the criminal underworld is well-documented, and extends beyond his songs to his film projects.

For example, the “Smooth Criminal” short film borrows from the narrative of the life of Jack ‘Legs’ Diamond, an Irish-American gangster based out of Philadelphia and New York City during the prohibition era.

During the final years of his life, Jackson had reportedly wanted to direct a full-length feature film based on the concept, even inviting longtime collaborative partner Kenny Ortega to join him as co-director on the project.

The song “Smooth Criminal” itself evolved from Jackson demo of the same era called “Al Capone,” named after the infamous Chicago-based gangster figure.

An unreleased version of Jackson’s “Al Capone” demo took inspiration from yet another gangster tale of the same era – the William R. Burnett-written book and subsequent 1931 film adaptation Little Caesar, which tells the story of a hoodlum who ascends the ranks of organised crime in Chicago until he reaches its upper echelons.

Directed by Mervyn LeRoy, and starring Edward G. Robinson in his breakout role as Caesar Enrico “Rico” Bandello (a.k.a. ‘Little Caesar’), the film includes the famous scene in which a defiant Rico shouts: “You want me? You’re going to have to come and get me!”

Producer and musician John Barnes, who helped Jackson bring “Al Capone” to fruition, sampled Rico’s words in the unreleased version of the track.

Together with producer and engineer Bill Bottrell, Barnes also sampled a series of gunshot sounds, as well as vocals from various James Brown songs.

The samples were pieced together and edited to create a virtual gangster-inspired duet between the King of Pop and the Godfather of Soul – something that Barnes says Jackson absolutely loved.

An even earlier song called “Chicago 1945” – which Jackson worked on during the Victory era with Toto band member Steve Porcaro – also makes reference to Al Capone in its lyrics.

And so when songwriter and producer Dr. Freeze came to Jackson with a demo called “Blue Gangsta,” the pop star was excited about the idea of resurrecting his fascination with gangster themes in his music.

Written by Freeze and recorded by Jackson during the very early Invincible sessions, “Blue Gangsta” originates from the same era as “Break of Dawn” and “A Place With No Name.”

All three songs were recorded by Jackson during his time collaborating with Freeze and engineer CJ deVillar at the Record Plant in 1998.

“I introduced him to many songs,” explains Freeze, who also worked with Jackson on a number of tracks that were never completed, including one called “Jungle.”

For “Blue Gangsta,” Freeze says:

“I wanted to make a new ‘Smooth Criminal.’ Something more modern and rooted in the 2000s. That was the idea.”

Freeze composed the original “Blue Gangsta” demo on his own – including the background vocals, synthesisers and horns – before presenting it to Jackson.

Then, once Jackson had given the demo his tick of approval, the pop star brought in some of the industry’s best session musicians to play on the track.

Brad Buxer – who did everything from digital edits to arrangements on all of Jackson’s albums from Dangerous in 1991 to The Ultimate Collection in 2004 – plays keyboards on the song.

Greg Phillinganes – who contributed his talents to each major studio album Jackson participated in between 1978 and 1997 (with the exception of Victory in 1984) – plays the Minimoog.

And legendary orchestrator Jerry Hey – who did the horn arrangements on everything Jackson did from 1978 to 1997 – fittingly leads the horn section on “Blue Gangsta.”

“The song was just awesome,” recalls engineer Michael Prince of “Blue Gangsta.”

Prince, along with arranger Brad Buxer, spent several years working on music with Jackson and Freeze.

“Michael obviously loved ‘Blue Gangsta’ because to bring in some of those musicians is very expensive,” says Prince.

“I mean, you’ve got Jerry Hey doing the horn arrangement – it’s no wonder the brass on ‘Blue Gangsta’ was so incredible.”

“Michael was the world’s biggest perfectionist,” says Buxer.

“Not only with music, but with sound. How loud it is. How it affects you. Where it hits your ear. What frequencies. A million things. So you’re not just talking about songs or mixing – you’re talking about arrangement, amplitude, and the instruments selected for the production.”

Talented percussionist Eric Anest – who played on a number of Jackson’s demos in the mid-to-late 90s, including “Beautiful Girl,” “The Way You Love Me” and “In The Back,” – was also given a copy of “Blue Gangsta” to see what he could bring to the table.

“Eric did wonderful percussion work,” recalls Buxer.

“Industrial types of percussion,” adds Prince, explaining that Jackson would never settle on an idea, sound or musician until he’d explored all the available options.

“Eric, Paulinho Da Costa or even Steve Porcaro might get the track for a day or two, and then send it back to us with forty tracks of what they’d added. Then we’d have to figure out what we were keeping, and what we weren’t. Sometimes we scratched it all.”

As previously noted by engineer Michael Prince, the caliber of session musicians used by Jackson on “Blue Gangsta” was a reflection of his love for the song. They weren’t just tinkering about the studio.

The same applies to the team of engineers who worked on it.

“Sonically, we always try to make sure we have pristine, detailed sounds,” explains Jackson, adding that he uses, “the best engineers and the best technicians available.”

And he wasn’t kidding.

Jackson recorded his lead vocals on the track were recorded by an all-star cast of engineers including CJ deVillar, Jeff Burns and Humberto Gatica.

Gatica in particular is one of the most acclaimed engineers in the history of modern music, having not only worked on Jackson’s Thriller, Bad, HIStory, and Invincible albums, but also on tracks with Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, Andrea Bocelli, Barbra Streisand and many others.

Engineer and musician, CJ deVillar, believes that it’s possible that Jackson was at the peak of his vocal powers during the “Blue Gangsta” recording sessions.

“He may have been in his prime at that time,” says deVillar.

“Michael was forty years old when he recorded ‘Blue Gangsta.’ His mental attitude combined with his physicality was at its height, in my opinion. The calisthenics he was pulling off and the way he worked the microphone… it was ridiculous!”

DeVillar continues:

“When I was in that chair recording him I felt totally educated. And usually I’m running it. I’m producing it. But I felt totally educated when recording him. The responsibility was enormous to me.”

“Working with Michael Jackson was amazing,” recalls engineer Jeff Burns of the recording sessions.

“He really is an American treasure and a once-in-a-lifetime talent. The first day I met him, we were recording his vocals. I was running the recorder for him that day and was a little bit nervous to do punch-ins on his vocals. I had worked with a few singers where I did lots of ‘punches’ on their vocal tracks to correct timing or pitch problems. Anyway, I was amazed when Michael started singing that his voice was in perfect pitch and was just pure and magical. I didn’t have to do any punches on his vocal – he sang it perfect all the way down.”

“His tone is insane,” adds deVillar.

“Insane! It would be impossible to not be able to mix his vocal correctly. And Michael was even good with his plosives; when you breathe and blow air on the microphone. Those sizzles, you know, they f*ck up a microphone. But Michael was in complete control of those things. Most singers are nowhere near his vicinity. Michael understood the process so well that when he would hear himself in playback in the studio over the years, he found a way to get rid of those problems. Because when you go from the vocal booth back to the control room and listen, it’s a different dynamic. The microphone sensitivity is different depending on how you hit it, and of course Michael knew that. So I never heard a plosive or sizzles that were over the top.”

DeVillar continues:

“By the time he recorded ‘Blue Gangsta’ you’re seeing thirty years of a genius molding his vocal sound to fit the records. There’s the youth and power in the voice, but then there’s the smarts. Michael had them both going on and I think they really peaked at that point when we were recording him. The smarts, the experience, and the power just married and it was incredible. I was just beside myself.”

While Jackson recorded his leads, Freeze completed his own vocals for the choruses and background harmonies.

Singing background vocals on the songs he writes and produces is Freeze’s signature, and he did it on all of the songs he recorded with Jackson, including “Break of Dawn” and “A Place With No Name.”

“Freeze would stack all his own backgrounds first,” explains engineer Michael Prince.

“And then Michael would come in and go: ‘That sounds perfect.’ Then he would sing one note of each of the harmonies so that there was a little bit of him on there too.”

From there, Jackson took a copy of “Blue Gangsta” home to study – to find areas that, in his artistic opinion, required improvement.

“It was incremental work,” recalls Freeze.

“He listened to the different mixes and changed some details around here or there. He was in full creative control.”

Jackson explains that when he listens to a work-in-progress copy of a song, his ears instantly identify everything that is missing.

“When you hear the playback, you think of everything that should be there that’s not there,” explains Jackson. “You’re hearing everything [in your head]. You wanna scream because you’re not hearing it [on the playback].”

Freeze recalls that when Jackson identified the missing pieces, they were added:

“When he returned [to the studio], changes were made and ideas were proposed. He listened attentively… Ultimately, all decisions were his. He was the boss. He was open to any criticism or suggestions beneficial to the song.”

Over time, several embellishments were made to the original recording.

For example, on March 6, 1999, Jackson wanted some very specific percussion sounds added to the track.

His instructions were so specific that Jackson had to phone Brad Buxer and Michael Prince at the Record One recording studio and have the call patched into Pro Tools in order to get down exactly what he was hearing in his head.

“We set it up so that Michael could just call and record straight into Pro Tools,” explains Prince, “so he wouldn’t have to carry a tape recorder around with him all the time to capture his ideas.”

With Jackson on the line, Buxer and Prince opened up the “Blue Gangsta” Pro Tools session and played the track.

Then Jackson, over the phone, proceeded to orally dictate the precise percussion sounds he was hearing in his head by beatboxing them over the track.

“That’s how we would get it in the actual session, in the exact spot MJ wanted it, with the exact timing he wanted,” explains Prince, who recorded the call while Buxer communicated back and forth with Jackson amidst his private beatbox master class.

Buxer: “Killer! Killer!” (to Jackson as he orally dictates the percussion)

Jackson: “You know what I mean, Brad?”

Buxer: “Yes, Michael.”

Jackson: “Are you hearing how I’m doing it?”

Buxer: “Yeah. It’s killer! Killer. We got it!”

The very next day, Jackson had a fleeting Spanish guitar sound in “Blue Gangsta” replaced with the country-and-western whistle sound made famous in the theme from the 1966 Sergio Leone film The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, which was composed by Ennio Morricone.

Jackson had previously used the sample in live renditions of “Dangerous” – a performance which also includes gunshot sounds as well as the “You’ve been hit by, you’ve be struck by” line from 1987’s studio version of “Smooth Criminal.”

“As I said, I wanted to make a new Smooth Criminal,” reiterates Freeze of “Blue Gangsta.”

“It was our objective – the new Smooth Criminal.”

Gunshots, whistles and beatbox percussion weren’t the most obscure sounds that Jackson experimented with in his music.

“Michael used to create sounds and put it in a record,” remembers Freeze.

“He’d thrown an egg on the floor and we’d record that… He would let me hear music from Africa, Japan, and Korea, and he would study this kind of stuff. He would really school me with that.”

Jackson explains that he’s inspired by music from every corner of the globe.

“I’ve been influenced by cultural music from all over the world. I’ve studied all types of music, from Africa to India to China to Japan. Music is music and it’s all beautiful. I’ve been influenced by all of those different cultures.”

After adding the whistle, Jackson also had the second half of the bridge extended so that it crescendoed with greater effect, allowing Freeze’s chorus vocals to slowly creep back in from underneath Jackson’s post-bridge vocal arrangement.

And after that, the song was shelved, remaining unreleased in Jackson’s vault for many years.

Then, in December 2006, two songs produced by American rap artist Tempamental emerged online – one called “Gangsta” and another called “No Friend Of Mine” – both of which were built around Jackson’s then-unreleased track “Blue Gangsta”.

The songs included rap verses from Tempamental, with “No Friend Of Mine” also featuring a verse by Pras of The Fugees.

This was the public’s first time hearing “Blue Gangsta,” albeit in a slightly abstract, reimagined way.

Tempamental’s “Gangsta” remix stays relatively true to Jackson’s arrangement, while “No Friend Of Mine” – the more popular of the two thanks to the highly publicised Pras feature and the song’s high-quality release via Myspace – rearranges the original track, repurposing Jackson’s first verse as the bridge.

Shortly after they appeared online, Jackson’s then manager, Raymone Bain, commented that Jackson had not released any new music, indicating that the pop star was not directly involved with either of the Tempamental tracks.

“When I heard this remix, I could not believe it,” Dr. Freeze recalls.

“Many people called me because of it. I don’t understand what happened. The concerning thing is that I don’t even know who released the song… Why did they do that? Where did this rap originate? In fact, we knew nothing about it – neither me nor Michael. We really don’t understand where this leak came from.”

“‘No Friend Of Mine’ is not the name of the song,” adds Freeze. “It’s just the chorus that contains these few words. ‘What you gonna do? You ain’t no friend of mine,’ was just the chorus. The real title is ‘Blue Gangsta.’ This highlights the ignorance of people who are causing the leaks on the Internet. They take the song and put it online without knowing its origin. The song was not presented to the public [the way it should have been]. A guy has just stolen the song, added a rap, and swung it on the internet. I was not even credited. It just landed here without any logical explanation.”

Four years later, in late 2010 – 18 months after Jackson’s death – the latest version of “Blue Gangsta” leaked online.

Four years later, on May 9, 2014, an earlier version of the original track was posthumously released by Epic Records as part of the Xscape album, along with a remix produced by Timbaland.

Engineer Michael Prince insists that the record label’s decision to release the more primitive ‘original’ version – lacking all the changes Jackson went on to make – doesn’t align with the pop star’s artistic vision for the song.

“Michael was involved in every nuance of every sound on the record,” explains Michael Prince, “from the hi-hat to the snare to the sticks. If those sounds are removed from the track, it immediately takes a step away from his vision.”

“He’s totally consistent,” adds arranger Brad Buxer.

“He’ll never say one day, ‘Take this part out,’ and then the next day [ask], ‘Where is that part?’ He’ll never do that. He’s totally consistent. So all you’ve got to do is be on your toes and you’ll have a blast working with him. I’ve worked with him for a long time and it’s been the most wonderful experience.”

Producer Dr. Freeze reflects on working with Jackson:

“He was simply the most wonderful person with whom you could ever dream of working… From dusk till dawn, he created sounds, melodies, and harmonies… He could do everything himself. Michael was truly a living instrument.”

“His artistry and inspiration was something you could feel in the air when he walked in the room,” recalls engineer Jeff Burns. “He really demanded the best work out of everyone around him, and that has impacted me to this day.”

“He not only taught me how to create songs correctly, but also gave me advice on the music industry as a whole,” adds Freeze.

“He was an absolute genius. I was fortunate to have learned from one of the greatest entertainers of all time. I try to apply his advice to the projects I undertake today. I try to keep the artistic spirit of Michael Jackson alive. It’s like I graduated from the university of Michael Jackson. There are not enough words to describe what I learned from the King of Pop.”

Damien Shields is the author of the book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault examining the King of Pop’s creative process, and the producer of the podcast The Genesis of Thriller which takes you inside the recording studio as Jackson and his team create the biggest selling album in music history.

Subscribe to Podcast

Articles

Producer Teddy Riley Comes Clean Regarding Fake Songs From Posthumous Michael Jackson Album

Legendary producer Teddy Riley has spoken out against the controversial Michael Jackson album he worked on after the pop star’s...

Huge Win for Michael Jackson Fan as Supreme Court Rejects Sony’s Free Speech Defense in “Fake” Songs Lawsuit

Two ‘get out of jail free’ cards, used by lawyers for Sony to avoid facing the music in a consumer...

Alleged Forgeries Removed From Michael Jackson’s Online Catalog After 12 Years of Protests and a Fraud Lawsuit

Three songs alleged to have been falsely attributed to Michael Jackson were abandoned by the pop star’s estate and record...

Supreme Court Judge Grills Sony Lawyer Over ‘Contradictory’ Arguments in Alleged Michael Jackson Fraud

A lawyer defending Sony Music and the Estate of Michael Jackson in a consumer fraud lawsuit has today argued that...

Court Date Set in Supreme Court Battle Over Legal Right to Sell Alleged Michael Jackson Forgeries

Sony Music and the Estate of Michael Jackson will again fight for their right to sell alleged forgeries as authentic...

Invincible, ‘Xscape’ and Michael Jackson’s Quest for Greatness

Below is a chapter from my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault, revised for this article. The full book...

‘Blue Gangsta’ and Michael Jackson’s Fascination with America’s 20th Century Underbelly

Below is a chapter from my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault, revised for this article. The full book...

Michael Jackson Meets America in Invincible Album Outtake ‘A Place With No Name’

Below is a chapter from my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault, revised for this article. The full book...

First Amendment Coalition to Support Sony and the Jackson Estate in Fake Songs Lawsuit

There has been yet another twist in the class action lawsuit filed by Californian consumer Vera Serova against Sony Music...

Californian Government Joins Fraud Lawsuit Against Sony Music and Jackson Estate

The California state government has officially joined a class action lawsuit against Michael Jackson’s estate and record company. In a...

GMRRA

October 1, 2013 at 6:59 pm

“Then Matt broke the number one rule that you never break – he gave Michael the master tape. And once you hand anything to Michael Jackson you may as well just chuck it off a pier because you’re never ever going to see it again.” <<<Hahahaha.

Always a joy to read your articles =)

Morinen

October 1, 2013 at 7:24 pm

For some reason I believed it was a pre- Thriller song – I think that’s how it’s marked in Vogel’s nook, ad OTW era. Is it possible that Sundberg didn’t know of its prior existence?

Jamon Bull

October 1, 2013 at 9:24 pm

I personally wouldn’t put a huge amount of stock in what Joe Vogel has to say. He went on record as calling the Cascio tracks ‘classic Michael’ and vouched heavily for their authenticity in his book ‘Man in the Music’. He actually has a lot of inaccuracies in his discussions around MJ’s art, not only in his book and reviews but in the Bad 25 documentary as well.

morinen

October 4, 2013 at 3:43 am

It’s simply not true, he didn’t vouch for them in the book. He commended on the controvercy giving both sides on the story and gave very brief comments on each track carefully choosing the phrasing to avoid alleging a specific writer or vocalist. You are biased.

Jamon Bull

October 4, 2013 at 11:58 am

I’ve been thinking a lot about my comment regarding Joe for the past day or so. I think I was a bit too aggressive there and I don’t think it was fair. And you’re right, I think I have been a little biased. I went back and re-read the particular chapter we were both referring to in his book. Read it for the first time since it came out. How I perceived it at the time was definitely different to how it reads when looking at it through the perspective you illustrated. Joe did choose his words carefully, he was being very subtle. For a long time I just threw anyone who remotely defended those tracks into the same category, and that was wrong. I’m still really raw about some issues and I think like many others, I will be until they’re resolved. Look I think Joe has written some wonderful things, I love a lot of Man in the Music and his piece on Earth Song is probably the most comprehensive discussion ever written around a single Michael Jackson song. So yeah, sorry for being too aggressive in that comment.

Austin

October 1, 2013 at 7:42 pm

Great article as always 🙂

Jamon Bull

October 1, 2013 at 9:29 pm

Another brilliant article, Damien. It’s great to learn about the songs creation and journey. I’d have loved to hear Michaels vision for the complete song. If the quality of his 2008-2009 work is anything to go by (Best of Joy), it would have turned out even more amazing than it already is! Thank-you for taking the time and effort to detail the process of Michael’s art for his fans. Keep doing what you’re doing!

Brad Sundberg

October 2, 2013 at 12:48 am

Great job Damien. I love that story and I appreciate your re-telling it. Morinen, truthfully I have not read Joe’s book (nor was interviewed!), but I know Joe does a great job of compiling as many facts and stories as possible. Michael was a very complex guy with a lot going on at any given time, so I try to avoid thinking or saying I know every detail about every song and project. Moon, however, according to my friend Matt Forger, was after Thriller and before Bad. I know many of Damien’s readers have grown up on CDs and iPods, so the crummy quality of a cassette pre-dates you. In the studio we went to great lengths to make every cassette for Michael, Quincy and Bruce sound as pristine as possible. Still, it would never be regarded as “master quality.” That is why I love this story, and this song, so much. As Damien stated, it shouldn’t work… but it did. Nice job.

Sheryl

October 2, 2013 at 1:55 am

Thanks, Brad, for your comments here. I enjoyed reading your words, also. Your professionalism is very apparent. No wonder Michael wanted to work with you.

Damien Shields

October 3, 2013 at 2:16 pm

Thanks Brad!

morinen

October 4, 2013 at 3:44 am

Thanks for commenting on this Brad! See you in Paris next week 🙂

Ashley

October 2, 2013 at 1:36 am

Amazing, as always!! :-)!!

Lauren

October 2, 2013 at 2:14 am

I love reading the history of little gems like Scared of the Moon. Thanks, Brad, for your input and knowledge. Just to set the record straight, Joe Vogel dates Scared of the Moon between Thriller and Bad, and credits Buz Kohan as co-writer. (Man in the Music pp. 128)

Damien Shields

October 3, 2013 at 2:15 pm

Yes, what Joe wrote is accurate.

Elke Hassell

October 2, 2013 at 2:43 am

Great Job once again Damien. And I sooooo love that song. I just played it and my hyper dogs fell asleep almost immediately with the soothing vocals of Michael and that my friend means something. Thanks for the info as always greatly appreciated.

Damien Shields

October 3, 2013 at 2:15 pm

Thank you 🙂

Cherubim

October 2, 2013 at 3:40 am

“Scared of the Moon” is a quiet Masterpiece!!!!

Chris

October 2, 2013 at 4:41 am

Thanks for the interesting details.

Would love to hear from Matt Forger (or Brad if he knows) what the inspiration was behind this song, “Scared of the Moon”. MJ’s storytelling was triggered by so many interesting things…

Damien Shields

October 3, 2013 at 2:15 pm

You’re welcome!

Judith Mason

October 2, 2013 at 5:13 am

Oh what a lovely song. It sounds like a lullaby and I can envision Michael perhaps singing it to his little children as they drift off to sleep.

TJ

October 3, 2013 at 3:40 am

This website is not only an excellent resource for current fans to learn about their idol, but the info that Damien collects & presents here will be helping people understand how Michael worked, and the specific journey of some of his songs, for decades to come.

*APPLAUSE*

Damien Shields

October 3, 2013 at 2:14 pm

Thanks brother. I truly appreciate your kind words. Documenting Michael’s art and legacy is very important to me. His legacy as the greatest recording artist and entertainer of all time is built around forty years of hard work and dedication to his craft. His art is what we’ll be talking about when we are old men and women sitting on rocking chairs. His art is what we’ll introduce our children and grandchildren to. That’s what will define Michael Jackson forever and for all time. Michael’s TRUE story is his music. It’s important that we get the story straight.

Mary Anthony

October 6, 2013 at 10:35 pm

I agree Damien

Anne Marie

October 3, 2013 at 4:12 pm

Damien, your articles take me to the place where Michael lives. In his music. In the HIStory of the music, away from the very public noise and pain of his loss. Thank you, and please continue!

Pauli D

October 6, 2013 at 10:49 pm

Great article, once again.

Thank you Damien

Heidi

October 12, 2013 at 8:23 pm

I am wondering, what was the little bit of work that was done for the song during the Invincible album sessions that Michael Prince spoke of. And why was it not applied?

natty

October 13, 2013 at 1:32 am