Creative Process

EXCLUSIVE: Inside Michael Jackson’s 1995 ‘One Night Only’ Special That Never Was

Published

10 years agoon

On July 25, 1995, pop superstar Michael Jackson revealed that he would be participating in a television special called Michael Jackson: One Night Only – an intimate concert to be filmed at New York’s Beacon Theatre on the 8th and 9th of December, before being exclusively aired on HBO at 8 P.M. on December 10.

One Night Only was ultimately cancelled just days before it was scheduled to be broadcast, with Jackson having been rushed to hospital after collapsing during rehearsals on December 6, 1995.

The cancellation of the special raised questions, many of which remain unanswered. To this day, fans continue to wonder about the show that never was.

Which songs Jackson would have performed? How the production would have looked? Were the rehearsals videotaped? Whose idea it was to do the show? Was Jackson’s collapse was legitimate, or staged? Why was the special never rescheduled? And what impact would it have had on Jackson’s life and career if it had actually taken place?

And so I decided to look into it, interviewing many of those involved with what might have been the greatest concert to never happen.

“He couldn’t have been more passionate about it,” Jackson’s then-manager, Jim Morey, tells me of his client’s enthusiasm for the concerts.

“It was his concept. What Michael wanted to do was something he had personally never done before. There was always a mountain to climb, and this HBO special was going to be unprecedented. It was completely controlled by Michael and his people. He picked the director. He picked the guest stars. This would have been yet another mountain Michael would have climbed, and something that no other entertainer could have accomplished.”

Jackson, whose HIStory album had come out just six weeks prior to the announcement, approached his long-time friend, veteran director and executive producer Jeff Margolis, to help him stage the event.

“Michael came to me. I’ve known him since he was a wee tot, and we worked many, many times together over the years,” says Margolis, who produced the Emmy Award-winning Sammy Davis, Jr. 60th Anniversary Celebration television special in 1990, and Happy Birthday Elizabeth: A Celebration of Life in 1997 – both of which Jackson performed in.

“He would come to my office occasionally, and I would go to Neverland Ranch, and we would just spend time together, talking about various things.”

“When Michael and his management company decided to do this, they really wanted to try something different,” he recalls.

“Instead of one of these giant arenas, Michael wanted to try and do something more intimate, and make him more touchable to his fans, and to the American public. So he came up with this idea, and came to me and said, ‘I want it to be intimate. How would you do it?’ And that’s how it came about.”

“We chose the Beacon Theatre in New York City,” adds Margolis.

“It’s a beautiful old artdeco theatre, and we wanted the intimacy of the theatre so that Michael could feel closer to the fans, and the fans could feel closer to him.”

“That’s what Michael had envisioned,” agrees Morey.

“Rather than him play Yankee Stadium in front of 70,000 people, the Beacon Theatre holds around 3,000 people, and it was this intimate view of Michael, not unlike what Frank Sinatra might have done. So it was going to be the man and his music, as opposed to lightning, flash pots, or gags.”

“I think that is the mark of a true performer, to be able to reach any audience around the world, any size,” said Jackson when asked about the notion of performing a more intimate show.

“If you can directly relate to a small group, magic starts to happen. I started out playing those kinds of concerts. [The HBO special] is intimate. It’s close-up. It will allow me to do a lot of things I’ve never done before.”

Once the concept and venue had been decided upon, Jackson and Margolis began to plan the show and assemble a team capable of helping them execute their vision.

“Basically, the music that was being done was whatever Michael felt was appropriate,” recalls Margolis.

“From his past hits, to his most recent material. He wanted to do a lot of past hits because everybody knew them. I hired the production designer I thought would be right, and the lighting designer that I thought would be right, and the choreographers.”

Margolis continues:

“I hired half-a-dozen choreographers on the show because we wanted each number to have a different feel. We didn’t want every number to look the same. Each choreographer had two or three numbers to design. I hired Jamie King (who did the posthumous Michael Jackson Cirque du Soleil shows), and I hired a choreographer called Barry Lather, who is Usher’s choreographer now.”

“I came in on behalf of MJ and Jeff as a consultant,” recalls Kenny Ortega, who produced several tours and performances for Jackson over the years.

“Jeff is a great friend and we worked together on many music driven projects.”

“I hired Kenny Ortega to supervise the whole thing,” explains Margolis.

“Kenny and I are really good friends and had done an awful lot of work together. He had worked with Michael before and I knew that Michael really, really liked him, and he loved working with Michael. And I thought, You know what? I’ll get him to come in and supervise all of the other choreographers. He’ll get it, and it made Michael feel comfortable that he was being watched over.”

Along with Ortega, Jackson’s long-time friend and dance icon, Debbie Allen, was also hired as a supervising choreographer.

“Since they knew each other so well I thought it would be fun to bring Debbie in,” recalls Margolis.

“Kenny and Debbie were there to help a bunch of young choreographers stay on task and keep our deadlines,” says Lavelle Smith Jr. – another of the choreographers involved with the show.

“Jeff Margolis needed people who he knew could help him talk to us as young dancers and choreographers.”

Smith, who co-choreographed the electrifying “Dangerous” routine performed by Jackson during the opening of the MTV Video Music Awards on September 7, 1995, recalls travelling to Europe with Jackson, his choreography partner Travis Payne, and an entourage of dancers for a promotional performance of the routine on German television show Wetten Dass – just five weeks before the HBO special was due to take place.

“Travis and I had just got back from Europe with Michael, and we hadn’t received a call about the HBO special yet,” recalls Smith.

“Michael was sure we had, because when we left Europe he said, ‘I’ll see you guys in New York,’ but we hadn’t got the call. So Michael had someone change our flights and the next thing we’re in New York.”

“I remember going to the first meeting with all the choreographers and thinking, What’s going on here?” says Smith.

“There were so many people there. Too many chefs in the kitchen, almost. Everyone was doing one or two numbers.”

“Were were told that we were going to develop an iconic TV show that would go down in history for Michael,” recalls choreographer Barry Lather.

“There were several choreographers involved, and there was an excitement that each choreographer was going to accomplish something extremely special and new for MJ; to develop new concepts, new dance moves, and create an epic television show.”

Dance rehearsals for the special would be held at Sony Studios in New York City, with up to one-hundred working dancers coming in and out of the building to rehearse their particular pieces.

“It was a team effort, but we all worked separately,” adds Lather.

“It had a top secret feel to me. Everyone doing their special performances, behind close doors. We didn’t view other choreographers work. It was definitely a unique project that everyone was committed to.”

“It was very compartmentalised,” says Smith.

“We were at Sony Studios with twenty-four dancers. We were keeping secrets from each other because we were all trying to make our numbers the best and blow each other out of the water. After the initial meeting I didn’t really see any of the other choreographers again. I saw Jeff Margolis a couple of times, and we saw Michael pretty much every day, but I think Jeff was just leaving us alone because he wanted it to be done so he could figure out how to shoot it. He gave us our space because he knew we were under a lot of pressure, and ‘Dangerous’ was going to be a big number.”

“All of his hair and makeup people, and his wardrobe people, had been talking to the choreographers,” explains Margolis.

“The choreographers knew what they needed for Michael Jackson, and what they needed for the dancers, and they relayed that all back to Michael Bush. They were all in sync. And Brad Buxer was coordinating the music with Michael, and Michael with the choreographers.”

“All of the dancing was being rehearsed at Sony Studios, and Brad Buxer was rehearsing the band somewhere else because he was using a symphony orchestra and they needed a bigger space to rehearse with them, so we couldn’t rehearse both things in the same place,” adds Margolis.

“But before Brad started rehearsing with the orchestra, he was at the dance rehearsal all the time, making sure that the rehearsal tracks were right and that the choreographers had what they needed. Everybody was in sync. The lighting director came and watched the rehearsals to make sure he knew how to light it properly.”

“Even though I was the executive producer and director of the show, there were certain things that were handled that I didn’t need to concern myself with,” explains Margolis.

“One of those was Brad Buxer’s area and anything to do with the music. He had that handled. I was responsible for the choreographers, Michael, and all that. Brad and his team took care of all the music. Michael Bush took care of all the wardrobe. The choreographers really worked closely with Michael Bush to get everything they needed. When I hire choreographers, I trust them. Most of them were television choreographers. They know what you can and can’t do for the television cameras and lighting; what kind of materials you can and can’t use in wardrobe. So those are things I don’t need to get involved in. I like to be in the loop and to see the designs before I see them on stage, which I did, but I didn’t have to be involved in the creative process.”

When re-imagining some of his classic dance numbers, Jackson and his choreographers sought inspiration from a variety of sources.

“For ‘Dangerous,’ we were inspired by the 1971 dystopian crime film A Clockwork Orange,” explains Smith, who co-choreographed the new piece with Travis Payne.

“The visuals, the colours, and moods you see in the movie.”

“It was going to be very stripped back,” he adds.

“I remember the music Brad Buxer had just given me. Without even trying, it was exactly what I asked for. It was like, wow. I just said strip it down. He did it once, I think I asked him to take more out, and finally we got there and I was like, That’s it! And it matched the movie, the vibe; it was just awesome.”

Of the new “Dangerous” composition, Smith explained that he and Payne were left with a very naked version at the beginning of the song:

“It’s even more naked than the versions Michael performed in Seoul and Munich in 1999. It doesn’t even sound like ‘Dangerous’ as we come onto the stage. And the guys: we’re like a group of crazed lunatics. If you’ve seen the movie, you’ll understand.”

“Michael loved the original ‘Dangerous’ number so much, but people were saying to him, ‘You do this number all the time. You have to change it. People are sick of it.’ So that’s where we were going with it; Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. It was gonna be sick. It was a funky vibe. Michael Bush went out and bought twenty-five bowler hats, the jockstraps, and we all had our own combat boots. We had the one eyelash and everything. We were going all the way.”

“It was a naked set, because we were the set,” explains Smith of the way the “Dangerous” performance would have appeared onstage.

“We wanted it that way. And it was kind of a Fosse stylised performance. Less is more. And we were going to have Naomi Campbell in it. She was going to come onstage for one walking pass. It was going to be awesome.”

“For some of the songs, he wanted dancers, and he wanted them very highly choreographed. And for some of the songs, he just wanted to be by himself on the stage,” remembers Margolis.

“And there were a couple of songs where I wanted him to be alone, and a couple where I wanted him to have full choreography, and we pretty much agreed on everything. His classic hits, like ‘Beat It,’ were done with dancers. I remember how brilliant the choreography was on that number.”

“Oh, yes,” remembers Smith of the new “Beat It” performance.

“Travis and I were working on that one. It was gonna include new stuff inside, with the classic dance moment at the end. You have to do the classic. The rest of the number, leading up to that point was going to be very Kung-Fu. We were inspired by Kung-Fu movies. Michael ordered us some Bruce Lee tapes. We were trying to get into that headspace.”

“It had to be exhausting for him, because on this show he didn’t just have one rehearsal a day; he had five or six,” adds Smith.

“It was a large undertaking. If he was the kind of artist that would stand and let people dance around him it would have been fine, but that’s not who he was. He had to be involved in the number. He had to inspire the number. And that’s a lot of pressure, and a lot of work. Our days were long, so I know his days were super long.”

One of the other numbers that Jackson was working diligently on learning and rehearsing was Barry Lather’s brand new interpretation of “Thriller”.

“For ‘Thriller’ I was thinking an industrial punk/rock vibe with a slight ‘spy’ undertone,” recalls Lather, who had previously worked with Jackson in 1986, as a dancer in Captain EO. “We had twenty dancers in trenchcoats, hats, and flashlight props. It was extremely specific, edgy and raw. I was trying to present ‘Thriller’ in a new way, which was a challenge.”

“The staging for ‘Thriller, as I mentioned, was very edgy and raw, with an industrial warehouse feel. Stark black and white tones and approach. It wasn’t a colorful performance, but bold intense rock-like lighting.”

“Michael totally learned all of the new ‘Thriller’ routine,” explained Lather in a 2012 interview with Christina Chaffin for Articlesbase.com.

“He learned the choreography when no one else was in the room. I was amazed how Michael learned by watching and soaking the choreography up visually.”

“He liked it alot, and was into mastering the new choreography,” Lather adds.

“There was specific staging, and new moves. The dancers and I had rehearsed for close to twelve days and had it all ready for Michael when he first viewed the performance and decided to learn it. I talked him through the performance; where the activity was unfolding, and the moments for him. When we showed Michael the routine, I danced in his place so he understood where the staging moments and attention was directed. That was really exciting and I remember being so detailed about everything. I wanted it to be perfect, and for him to like the performance and choreography.”

In fact, Jackson loved the new “Thriller” routine so much that he repurposed a number of Lather’s steps in his 1996 film Ghosts.

As well as “Thriller,” Lather was also tasked with reimagining “Smooth Criminal,” which he did.

Unfortunately, however, it didn’t catch on and was never fully realised.

“I had a new concept for ‘Smooth Criminal’ as well, but we didn’t get into that in rehearsals and develop that to the new concept,” explains Lather.

“But it was totally different and a new direction for that song.”

One Night Only was a departure from the typical rock concert style of performances Jackson had been giving on tour for the past decade, and so the staging and set were much different from what fans were used to seeing from the King of Pop.

“The set was really lovely,” explains Margolis.

“It was a full orchestra wrapped around the stage, and the back part of it was two storeys high; musicians on the second storey and more musicians below. And then the two side parts were his regular band. It was Brad Buxer and all the guys that normally played with him,” including Ricky Lawson on drums, David Williams and Jennifer Batten on guitar, and Siedah Garrett on background vocals.

“It was pretty spectacular,” continues Margolis.

“The lighting designer worked with the set designer, and it was lit in a way so that the band could be featured, they could be in silhouette, or they could disappear. And when they disappeared the set became a beautiful starry sky. It looked like Michael was floating in space. The floor was a shiny black floor, and everything else was like you were looking up into a star-lit sky. It was pretty amazing.”

“We had even built a little satellite stage out in the middle of the audience, off of the main stage, so that he could get out there to do one or two numbers and just be able to touch the audience, and they’d be able to touch him. It was really spectacular. It was really warm and intimate. It was a circular stage in the middle of the audience. It was very small, connected to the main stage by a runway.”

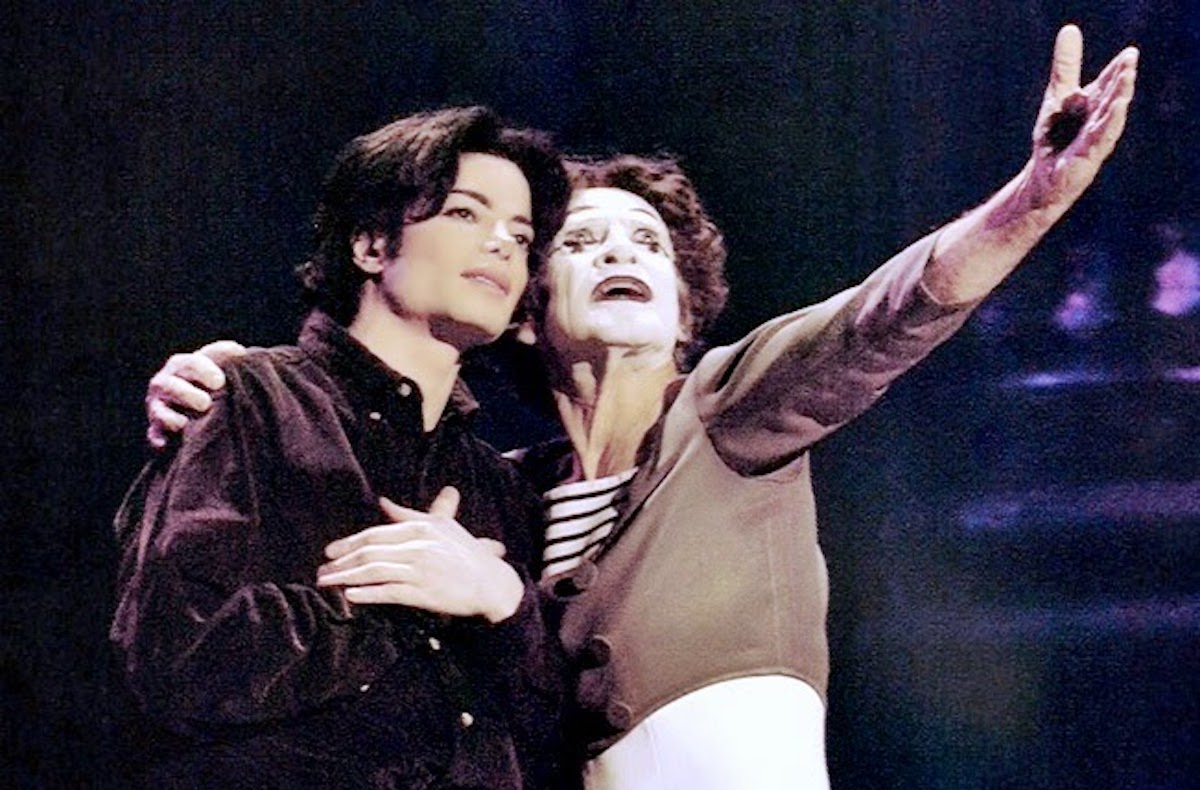

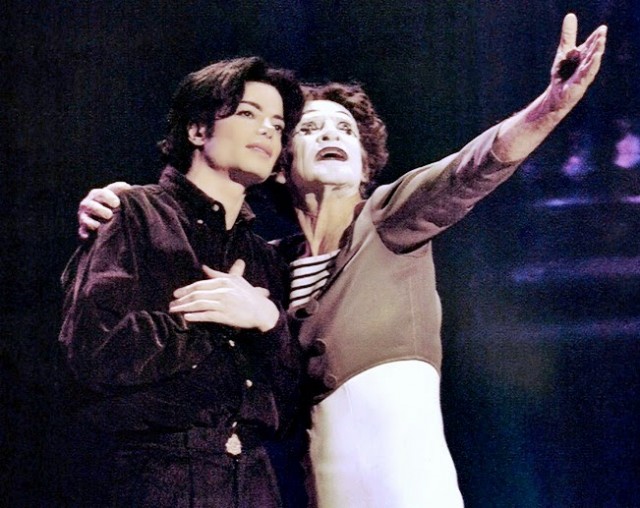

The most highly-publicised number set to take place during the One Night Only concerts was Jackson’s rendition of “Childhood,” featuring a special guest appearance by legendary French mime Marcel Marceau.

“He originally wasn’t going to have any special guests at all,” adds Margolis.

“This was going to be Michael’s moment to shine. It was going to be wall-to-wall Michael. And then he came up with this brilliant idea for Marcel Marceau to mime ‘Childhood,’ and it was brilliant. He was the perfect guest for this show.”

“He appreciates poetry in slow motion mime,” recalled Marceau in a 1996 interview with History magazine.

“He said he had written a song called ‘Childhood’. ‘I would love if you could take this song on stage,” he said, ‘and I’d do it with you. The slow movement of his character would be wonderful.’”

Marceau agreed to collaborate with Jackson on the piece and the two began discussing the logistics.

“When you are on the phone, a verbal agreement is far from a contract, after all,” explained Marceau.

“So I said, ‘Michael, I’ll give you my number in Paris. Call me if you like, and if we do it together, with a script.’ Not long after this conversation, he called me at home. He began to sing the song over the phone. I asked, ‘How do you see we will do this together? Send me a script,’ to which he replied ‘No. I want you to do the choreography and we will do it together. I’ll have to prepare a contract.’”

“Michael adored him a lot, and it was quite a negotiation on my part to be able to get him to do it,” recalls Morey.

“He was someone who just did not do guest appearances. I recall Marcel Marceau saying to me, ‘What exactly is it that Michael wants to do?’ And I said, I really don’t know yet, but momentarily we’ll get together and the two of you will figure it out. It was a difficult negotiation with his manager, getting him to agree to do something without being able to tell him what it was he was going to do. I said something along the lines of, ‘Surely two of the greatest creative geniuses of the world can get in a room together and figure out something to do.’”

Once the contract had been successfully negotiated by Morey, Marceau was flown to the United States to begin working with Jackson.

“I was greeted by Michael Jackson in great shape. He was happy to have me, and we started working immediately,” recalled Marceau.

“[He] wanted something concrete. Mimicking is cryptic; you can not imitate gestures in a song, there must be some kind of operetta, and ‘Childhood’ is a great song lyric flight. For this particular version of ‘Childhood,’ Michael said I was free to do what I wanted. Yet at the same time, I asked Michael if he liked what he was doing with his song, so you could say that we have worked together. I did everything [in New York City]. Direct contact with Michael was essential.”

“The stage was pitch black, Michael was in one pool of light, and Marcel Marceau was in another pool of light,” Margolis explains.

“That’s all the lighting there was. Michael was a little bit upstage of Marcel, and in a slightly smaller pool of light. Marcel was dancing downstage in a larger pool of light, because he had more movement. Michael stood and sang the song, and Marcel mimed to the lyrics. It was breathtaking.”

“There is in particular a passage (in ‘Childhood’) in which he speaks of pirates, kings and conquests,” explained Marceau.

“To make the transformation of a pirate to a king on stage; only mime… Mime, after all, is the art of metamorphosis. It is hard to do for a dancer. Michael has seen my work, and knows that I can express the major themes and concepts.”

“At the end of our number for ‘Childhood’ – a duet – he came to me singing ‘Have you seen my childhood?’ And with a wave of his hand showed the way. We ended the piece together… as one body in motion together. It was very, very pure. Poetic. To me, Michael Jackson is a true poet; a great poet of song. [He] is also an extraordinary dancer, and a showman with a great respect for the theater, music, and film. Michael [was] very happy with the work we did together on ‘Childhood’.”

“It’s wonderful! I adore this version of Childhood,” expressed Jackson in an interview years later.

“It’s strange, nobody ever saw it. There are things like that which nobody will ever see. It was wonderful!”

“Marcel was Michael’s only celebrity guest on the show,” recalls Margolis.

“It was one of the most brilliant pieces of television that I have ever been involved in.”

Other planned numbers that the world never got to see include brand new choreographed renditions of “The Way You Make Me Feel” and “Bad,” plus performances of “Earth Song,” “You Are Not Alone,” “Black or White,” “Smooth Criminal,” and “Smile”.

“There was a beautiful girl that Michael was going to do a solo dance routine with,” recalls Morey.

“She was someone that Jeff Margolis introduced Michael and I to. I don’t recall her name, but I remember that she was very beautiful, very talented, and that Michael was really quite smitten with her.”

“The rest of the time it was Michael, Michael, Michael,” says Margolis.

“And that’s what it was supposed to be. And you were going to see every side of Michael that you could possibly imagine in those two hours.”

There was even talk of Jackson doing all-new choreography for “Billie Jean,” which had become perhaps his most iconic dance number of all by that time.

“I remember them trying to get him to do that,” recalls Smith.

“But why? They were trying to get him to change everything. From his dance routines to his hair.”

It’s entirely possible that Jackson was indeed going to debut a new version of “Billie Jean” during the One Night Only special.

Years later, when asked what his favourite song to perform was, Jackson said that “Billie Jean” was:

“But only when I don’t have to do it the same way. The audience wants a certain thing. I have to do the moonwalk in that spot. I’d like to do a different version.”

“Michael was smart,” says Smith.

“He would have done whatever he wanted in the end. If the new numbers weren’t ready he would just say okay, let’s go to the classic. And people wanna see him do the classics. Even if the new stuff is really good, they’re gonna miss the classics.”

Despite the fact that the HBO special was geared around being an intimate, no frills, “just the man, just the moves, just the music” event, Jackson and his team were toying with the idea of a spectacular special effects-assisted entry to the stage.

Similarly to the way he kicked off each HIStory tour concert less than a year later, Jackson was interested in a virtual video intro in which he found himself flying to the venue for the performance, with the video transitioning into to his in-the-flesh appearance onstage.

“He did have a thing planned for a model to fly over New York City,” recalls Morey.

“It would have been as if Michael had jet-packed out of a stadium some place, over the city, and found himself at this lovely little theatre in downtown New York to do a show. But it couldn’t have physically been done; it would have been done with special effects.”

Then, recalls Margolis, Jackson was going to surprise the audience by coming through one of the lobby doors on the jet-pack:

“He was going to fly over the audience and land on the stage. The special effects people who have always taken care of Michael’s rockets, and his flying up in the air and all that were involved. It was a much smaller version of what he would do in a big stadium. When you’re doing something like that in an indoor venue you’ve got to get permits from the police department and the fire department. We were limited with what we could do, so it was a mini version of what he had done in the past, but this time it was going to be him flying it.”

As the weeks became days, and the December 8 and 9 filming dates drew closer and closer, it was becoming clear that while some of the new numbers, like “Thriller,” were ready to go, others were not.

In the end, a number of the new routines, including Smith and Payne’s “Clockwork Orange Dangerous” (as Jackson called it), would not be included in the show.

“I kept getting the feeling that he either felt overwhelmed, or unsure about some of the numbers,” recalls Smith.

“We were going really slowly because we wanted it to be as good as it could be, but we didn’t have our normal amount of time to prepare.”

“It got to a point where they gave us a deadline and said everything has to be done in three days, which was fair enough,” adds Smith.

“So Michael said, ‘You know what? We’re gonna do the old Dangerous.’ Most of the dancers knew it, and we taught the ones that didn’t. It was gonna be the classic Michael Jackson ‘Dangerous,’ because he just loved it, and he knew it like the back of his hand.”

Smith continues:

“If it was new, and not as good as the original, it would’ve been taken out and he would have replaced it with a classic version of it. And then the ones that were good, like “Thriller,” would have stayed. The new “Thriller” was really good. I know Michael liked that a lot. So I think it would have been an amazing show, even if everything wasn’t new. You’d have had some new and some old together. It would have been awesome.”

The feeling that the show, and certain numbers, were not coming together in time to be included in the show was due in part to the fact that – as Smith and Lather expressed – the entire process was so compartmentalised that no one knew what the other was doing, or how far along in the process they were.

“Everybody never got into the same place at the same time until we moved into the Beacon Theatre,” explains Margolis.

“We were at the Beacon for a total of about seven days. By the time we got the set in, and lit, and got all the technical equipment in. I think we rehearsed on the stage for four days, and Michael wasn’t there the first day as it was mostly a dance rehearsal for the dancers to find their spacing on the stage. And then Michael came in and rehearsed the second, third and fourth day. The first day that Michael was there he did a half-day, and the second and third days were full days for him.”

Just before 5 P.M. on December 6, during the second of several planned full-day dress rehearsals at the Beacon Theatre, and just two days after he and Marcel Marceau had fronted the media to promote the HBO special, Jackson collapsed on stage.

“He was already feeling ill and had been sick for a few days,” recalls Lather, who had camera blocked his new “Thriller” performance with Jackson onstage earlier that day.

“Later that afternoon when we were doing additional camera blocking, he collapsed on stage and had to immediately go to the hospital.”

While Lather says that Jackson had been feeling unwell for a few days, Marceau, who was also rehearsing with Jackson in the days leading to his collapse, and was present to witness it, did not detect any ailment on Jackson’s part.

“I would have noticed something,” recalled Marceau.

“There was no sign that he was on the verge of a crisis… I was in the Beacon Theatre, watching the [rehearsals], which were wonderful. Michael was on stage with about fifteen dancers. At one point I turned away to get something to drink and then, suddenly, there was a great silence. He stopped everything. Just before the music was loud, the lights flash, and then, in a moment there was total silence, it was as if the world had come to an end.”

“We were all standing on stage,” remembers Smith, “and saw him walk to the front of the stage and go down, hitting his face on the grating of the stage.”

“He had both hands by his side, with the microphone in one, and fell face-first onto the metal grate,” recalls Michael Prince, one of the show’s sound engineers.

“He didn’t even put his hands out to break his fall. It was scary. And he fell down hard. I’m surprised he didn’t break his nose or his jaw on the grate.”

The metal grate is part of the stage that is specially built into the floor. Jackson uses this to create an effect in certain numbers, including “Black or White,” with bright light, wind, and smoke blasting out from beneath him. Witnesses recall that it was during camera blocking for “Black or White” that Jackson’s collapse took place.

“He was out,” says Margolis.

“He fell so hard, and smacked his head on the grates so hard, that he was out cold.”

“He had collapsed, lost consciousness, and was on the floor,” recalls Marceau.

“We were all petrified. There were people around him, he did not move at all. Paramedics arrived, and when I saw the stage I was very scared.”

“His bodyguards rushed over and formed a protective circle around him, holding their jackets up to give him some privacy,” recalls Prince.

“Someone yelled for an ambulance and, within minutes, one arrived.”

“I’m the one who called 9-1-1,” recalls Morey.

“He was breathing, but definitely not responding. I thought maybe he’d had a heart attack.”

“I must say that the 9-1-1 responders, even with the traffic in that city, got to the Beacon Theatre in less than five minutes. It was incredible,” says Margolis.

“First they checked him out as he lay on the ground, then they had him on a gurney, in an ambulance, and out of there so fast. They moved like bullets.”

Jackson was rushed to Beth Israel Medical Center North at 170 East End Avenue on the Upper East Side of New York. Meanwhile, a meeting was called in the lobby at the Beacon Theatre.

Prince recalls that once Jackson had been whisked off to the hospital, an announcement was made over the PA system at the Beacon asking all dancers, band, cast and crew to gather in the theatre’s lobby.

“It seemed that probably this whole show was going to be cancelled or delayed somehow,” recalls Lather.

“No one knew what was going to happen for the rest of that day. We were still camera blocking and putting the show together with Jeff Margolis. The entire show was never ran from beginning to end; the production wasn’t ready for that yet. Several more days of camera blocking were still on the schedule.”

Ultimately it was decided that the show, or at least rehearsals at that point, would go on without Jackson, who was not scheduled to be at the Beacon Theatre that evening anyway.

Jackson was scheduled to attend the 1995 Billboard Music Awards at the New York Coliseum that evening, where he was to receive the Special Hot 100 Award for his outstanding chart achievements.

Instead, Jackson lay in a hospital bed, with medical professionals working to stabilise him.

The One Night Only cast and crew continued to run numbers and camera block at the Beacon Theatre that evening, and the next day, as Jackson awaited the arrival of his personal physician, Dr. Allan Metzger, who was flying to New York from Los Angeles to assess the superstar.

Vice President of Media Relations at HBO, Quentin Schaffer, issued a brief statement on the evening of the collapse, letting the public know that Jackson had been “stabilised,” while confirming that rehearsals were continuing. Schaffer acknowledged that the status of the special was uncertain, adding that HBO’s main concern was Jackson’s health.

Jackson’s blood pressure was found to be an abnormally low 70 over 40 by an Emergency Medical Service crew that arrived at the Beacon Theatre just four minutes after the collapse, reported John Hanchar, a spokesperson for the E.M.S.

Dr. William Alleyne II was the Critical Care Director at Beth Israel North Hospital in December 1995, and was responsible for providing the medical care that ultimately saved the King of Pop’s life.

“Mr. Jackson was in critical condition,” Alleyne told Herald Online.

“He was dehydrated. He had low blood pressure. He had a rapid heart rate.”

Meanwhile, the public had caught wind of Jackson’s situation, and began to gather in droves outside the hospital to show their support for the superstar.

“I looked outside the window, and the crowd was shoulder-to-shoulder, huge, far more than when the mayor’s mansion across the street had hosted the Pope, the President, even Nelson Mandela,” Alleyne recalled, adding that it was even “absolute pandemonium” inside the hospital.

It didn’t take long for the media to start reporting the incident, with speculation over the severity of Jackson’s condition running rampant.

“Michael Jackson Collapses At Rehearsal,” was the New York Times’ headline the next morning, reporting that Jackson collapsed while rehearsing on stage the afternoon before, “casting uncertainty over plans for a highly publicised national cable television special to be telecast on Sunday.”

Entertainment Weekly took the news of Jackson’s collapse with a grain of salt, running a story that asked: “Did Jacko faint on stage–or stage a faint?”

The EW article claimed that an unnamed source had revealed to them that Jackson was displeased that the streets of New York City had not gone into lockdown over his concerts, and that the 2,800-seat Beacon Theatre was so small it was incapable of facilitating Jackson’s enormous lighting setup – neither of which were true.

Jackson’s sister, LaToya, was quick to phone the New York Daily News with the assertion that she knows “all of Michael’s little moves and his little schemes that he pulls when he thinks he needs attention,” adding that his collapse was “a publicity move.”

“I don’t think anyone is a good enough actor to fake going down the way he went down,” says Prince, who witnessed Jackson’s dramatic collapse from his post with the sound crew.

The King of Pop’s doctor also insists his collapse was both very real and very serious. “He was near death,” stressed Alleyne, adding that Jackson “was unconscious when he arrived” at Beth Israel North Hospital.

“His biggest concern was could he perform,” recalls Alleyne of Jackson.

Unfortunately for all involved, Alleyne informed Jackson that there was “no way” he could perform anytime soon.

Jackson remained hospitalised and under strict medical care throughout the planned December 8 and 9 taping nights, and beyond HBO’s December 10 broadcast date, resulting in the cancellation of the whole thing.

Not only was Jackson’s collapse, and subsequent cancellation of the HBO special, seriously detrimental to his health, but it also damaged his future record sales in the U.S., and tainted the American public’s perception of his ability to perform live anymore.

“Without a doubt, the HBO special, we perceived, would have been a very big boost to sales right the way through to Christmas,” Vice President of Marketing at HMV, Alan McDonald, told The New York Times.

“Jackson has run out of gas,” New York media analyst, Porter Bibb, said at the time, adding that he “may have seen his day as the King of Pop.”

On December 8, 1995, just hours before the first show was scheduled to take the stage with a live audience, the cast and crew at the Beacon Theatre were again asked to assemble themselves for a meeting, with Margolis delivering the news that no one wanted to hear.

The show would not go on.

“We got the word that it was being cancelled,” recalls Lather.

“It was so disappointing, because everyone had worked so hard, and so many creative special people were working on the show to accomplish something never seen before for Michael.”

“In hindsight, it’s really eerie that my career working with MJ was bookended by cancelled concerts,” recalls Prince, whose first-ever gig with Jackson was One Night Only, while his last was the ill-fated This Is It.

Once the cancellation had been confirmed, attention was turned towards whether or not the show would be rescheduled at a later date.

“The show was pretty much ready to go,” recalls Margolis.

“I mentioned it at one point to his management that when his health got better we could try and redo it. They said that they would discuss it with Michael and then I never heard back from anybody about anything. But yeah, the music was all done. The mixes were all cleared. The orchestrations were all done. Everything was finished. It was a done deal. And for some reason it just never happened. I guess when HBO and everybody said ‘one night only’ they weren’t kidding.”

The lack of rescheduling was less due to HBO’s desire to try again, and more so a combination of Jackson’s hesitence to return to the concept, and the insurance company’s settlement of HBO’s claim.

“HBO had insurance on the shows,” explains Morey.

“So the insurance agency got involved. Basically, once the show became an insurance claim, the whole concept just went away.”

During a 1996 interview, Jackson was asked whether or not he was still planning to tape the HBO shows.

“Oh, yes,” Jackson responded hesitantly.

“We’re planning on doing that in Africa. In South Africa.”

I asked Margolis if he’d heard about that. His response:

“No. I know nothing about that.”

“That sounds like Michael Jackson hyperbole, really,” Morey agreed.

“There was no discussion of doing it in Africa – or anywhere.”

“No,” added Smith.

“It was too much. We never talked about it again. He did mention that he loved the new Clockwork Orange ‘Dangerous,’ and he said he wished we could have done it. But no, he never talked about doing the HBO special again.”

Years later, Jackson was again asked about the cancelled shows, and whether he would ever do them.

“No, I don’t think so,” Jackson told Black and White magazine.

“I worked so much to prepare that show, there was such a pressure; people pushing me to do this show no matter what! Then, finally, the nature took its course and said, “stop!” She decided I shouldn’t do that show.”

Although Jackson never agreed to revisit the show, there is a small glimmer of hope that fans will see it one day. Rehearsals for One Night Only were – as has long been speculated – captured on tape.

“Michael wanted to look at everything,” reveals Margolis.

“Everything during rehearsal was taped. Michael had his own film crew documenting everything that he did. Often when he would do a performance he would ask the director of the show for a copy of his rehearsal to be able to take home and study, to see what he could improve on. He was such a perfectionist.”

“He gave us cameras and we shot, and we would give him the footage to study,” explains Smith of Jackson.

“There was a lot of shooting going on by me and Travis. Michael’s crew was there when he was there, and he was with us a lot. They would set up in a place where we couldn’t see them, which I thought was nice, and we would all just do our thing and be ourselves.”

But! There’s a problem.

“The tapes have vanished,” says Margolis.

“They’ve disappeared. Michael ended up with all of the tapes. That was part of his agreement. HBO has nothing. His management company has nothing. His lawyers have nothing. I have nothing. Nobody had anything, except for Michael, and needless to say, they disappeared years ago.”

Jackson was infamous for losing important materials.

“Once you hand anything to Michael Jackson you may as well just chuck it off a pier,” says Brad Sundberg, one of Jackson’s most trusted studio engineers, “because you’re never, ever going to see it again.”

“When they cleaned out Neverland, I’m sure that somewhere on that estate he had a library that had every single piece of footage, and every single audio tape that anybody ever gave him, that fell into the Michael Jackson black hole,” speculates Margolis.

“Knowing Michael, and knowing how much of a perfectionist he was, I’m sure all of the One Night Only stuff was filed somewhere.”

As is seen in the footage captured during the lead-up to his ill-fated 2009 concert series, This Is It, and in leaked footage from preparations for the Dangerous tour, Jackson’s rehearsal tapes make for compelling viewing.

“Michael always looks presentable,” says Margolis.

“So even when he came to rehearsal, his hair and makeup was always done, and he had his hat and all that, because he was always being filmed. His own crew was always filming him so he was always camera-ready. So even if you looked at the rehearsal footage, it looked like a proper show. If anybody could find that footage and put it together, you could actually make a show out of it. Any time Michael was in rehearsal, it was documented. To see it again would be absolutely fantastic.”

“We were doing dress rehearsals when he collapsed, and even that was caught on tape,” adds Margolis.

“For every number, the dancers were in the wardrobe they were supposed to be in for the show. It was such a disaster. I wept when I found out we were never going to be able to do the show. It was going to be magical.”

“We were all there for him, and to make history,” recalls Lather.

“Jeff Margolis had worked hard preparing this show. It was going to be amazing. We all felt like this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. We were all in it together for Michael. We all felt honored to be working on this show! That was definite. There was this buzz in the air that this was going to be another major highlight in Michael’s career; a show talked about for years to come.”

“Had the special gone on the air, the viewer would have seen things they’d never seen before,” says Morey.

“There would have been things that would have been talked about the world over; from the water cooler or coffee station in every office, to the dinner table in every home. After the U.S. it would have eventually been broadcast all over the world.”

“I remember the feeling of doing it,” recalls Smith.

“It was just an awesome, awesome feeling. If we could have pulled it off, it would have shined from the heavens. It would have been glorious.”

Damien Shields is the author of the book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault examining the King of Pop’s creative process, and the producer of the podcast The Genesis of Thriller which takes you inside the recording studio as Jackson and his team create the biggest selling album in music history.

Creative Process

Invincible, ‘Xscape’ and Michael Jackson’s Quest for Greatness

Published

3 years agoon

October 30, 2021

Below is a chapter from my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault, revised for this article. The full book is available via Amazon and iBooks.

In order to fully appreciate the origins and evolution of “Xscape” – an outtake recorded for Michael Jackson’s Invincible album – it’s important to first understand Jackson’s relationship with its co-writers.

The journey begins in early 1999, when in-demand producer Rodney ‘Darkchild’ Jerkins received a phone call from renowned songwriter Carole Bayer Sager.

Bayer Sager’s working relationship with Michael Jackson dates back to the late 1970s, when she and producer David Foster co-wrote “It’s The Falling In Love” – a duet recorded by Jackson and R&B star Patti Austin, which was released on Jackson’s Off The Wall album in 1979.

Two decades later, Jackson and Bayer Sager were again working together.

During her 1999 phone call with Jerkins, Bayer Sager explained that she and Jackson were writing songs for Jackson’s next studio album at her home in Los Angeles, and that they wanted Jerkins to join them.

“He was this guy who went around Hollywood, and around the industry, saying his dream was to work with me,” explains Jackson.

“I was at Carol Bayer Sager’s house, who is this great songwriter who has won several Academy Awards for her songwriting, and she said: ‘There’s a guy you should work with… His name is Rodney Jerkins. He’s been crying to me, begging to meet you. Why don’t you pick up the phone and say hi to him?’”

Jerkins recalls that in the end, Bayer Sager made the call:

“Carole called me and said that she was gonna have a writing session at her house with Michael Jackson and she wanted me to do a track. I was like, are you serious?”

And so the producer immediately booked a flight from New Jersey to Los Angeles and headed straight to Bayer Sager’s home.

“I went over there and it was just an amazing experience. I was in awe,” recalls Jerkins.

“I’ve always heard people that worked with him say, ‘When you meet Michael, it’s crazy!’ But I’m the type of guy who’s like nah, I’ma be okay, I’ma be cool. It’s just another artist. And then once I got there, and was in his presence, I was like whoa, this is crazy!”

Jerkins explains that not seeing Jackson at the industry events or private parties added to his untouchable mystique, but that once the pair got in the studio together a friendship was born:

“Once I got in the studio, and once he felt comfortable with me, and I felt comfortable with him, it was like the best thing ever. And we just built a really solid friendship throughout the years. And we stayed working and stayed in contact and he was just a great guy.”

But the collaborative relationship between Jackson and Jerkins almost didn’t come to fruition.

Jackson recalls that when he met Jerkins at Carole Bayer Sager’s home in early 1999, Jerkins asked Jackson if he could have two weeks to work on a collection of ideas to present to him:

“He came over that day and he said, ‘Please, my dream is to work with you. Will you give me two weeks and I’ll see what I can come up with.”

Two weeks later, Jackson met with Jerkins for a second time, and Jerkins played him the collection of tracks he’d come up with.

“The day that Rodney met with Michael, he played him all these records,” recalls Cory Rooney – a songwriter and producer who was working as the Senior Vice President of Sony Music at the time.

“Michael was like, ‘It’s not that the guy’s not talented, but everything he plays me sounds typical. Like Brandy and Monica,’ whom Rodney had worked with previously.”

According to Rooney, the pop star didn’t want to fit in with the current industry sound of the time. Jackson wanted to pioneer his own new sound.

“And Michael just said, ‘I don’t wanna sound like Brandy and Monica. I need a new Michael sound. Big energy.’ And this is after Rodney played him twenty records.”

At this point, Jackson wasn’t sure whether Jerkins was the right man for the job.

“So Michael came back to me and said, ‘I don’t know if he’s the guy.’ And I was so sure that Rodney Jerkins was the most rhythmic, hard-hitting sound out there in terms of producers – other than Teddy Riley who was that at one point for Michael – I just said this is the guy. Rodney’s the guy.”

Rooney’s belief that Jerkins could essentially be Jackson’s ‘new Teddy Riley’ was no coincidence given that Jerkins grew up idolising Riley’s production style.

“Teddy Riley was the producer that changed my life,” recalls Jerkins.

“I remember being eleven years old and trying to emulate Teddy Riley. He was everything. He was everything to my career. Then having the opportunity to meet him at fourteen years old, and to play my music for him, and him telling me that I was good enough to make it was the inspiration and extra encouragement that I needed to know that this was real; that I wasn’t just some kid in a basement trying to make beats, but actually someone who could have a career.”

Riley went on to mentor Jerkins for years, and was reportedly responsible for Jerkins’ first encounter with the King of Pop at age sixteen, five years before he got the chance to work with Jackson.

And so despite his reservations, based on Rooney’s strong recommendation that Jerkins could deliver, Jackson remained open-minded about working with the producer.

“So Michael said, ‘I’ll tell you what, Cory. Do you think Rodney would mind me telling him that he kind of needs to reinvent himself for me?’” recalls Rooney.

“I said of course Rodney wouldn’t mind. I said I’ll have the conversation with Rodney, then you can have the conversation with Rodney. So I went, on my own, and talked to Rodney and told him what Michael felt.”

Following Rooney’s heart-to-heart conversation with Jerkins, the producer met again with Jackson. Rooney recalls:

“At that point, Michael set up the meeting and said to Rodney, ‘I want you to go to your studio and I want you to take every instrument, and every sound that you use, and throw it away. And I want you to come up with some new sounds. Even if it means you’ve gotta bang on tables and hit bottles together and make new sounds. Do whatever you’ve gotta do to come up with new sounds and use those new sounds to create rhythmic big energy for me.’ Michael put the challenge to Rodney, and Rodney accepted.”

“I remember having the guys go back in and create more innovative sounds,” recalls Jackson.

“A lot of the sounds aren’t sounds from keyboards. We go out and make our own sounds. We hit on things, we beat on things. They are pretty much programmed into the machines. So nobody can duplicate what we do. We make them with our own hands, we find things and we create things. And that’s the most important thing, to be a pioneer. To be an innovator.”

“He changed my whole perception of what creativity in a song was about,” explains Jerkins.

“I used to think making a song was about just sitting at the piano and writing progressions and melodies. I’ll never forget this crazy story. Michael called me and says, ‘Why can’t we create new sounds?’ I said, what do you mean? He was like, ‘Someone created the drum, right? Someone created a piano. Why can’t we create the next instrument?’ Now you gotta think about this. This is a guy – forty years old – who has literally done everything that you can think of, but is still hungry enough to say ‘I wanna create an instrument.’ It’s crazy.”

Jerkins recalls that following Jackson’s orders, he went out and began sampling sounds to use in their records:

“I went to a local junkyard and I started gathering trash cans and different things, and I began to hit on them to try to find sounds. Michael told me to. Michael said, ‘Go out in the field.’ That was his term. He used to say, ‘Go out in the field and get sounds. Don’t do it like everybody else and go to a store and buy equipment. Go out in the field and get sounds.’ So I went out in the field and got sounds.”

After building a library of junkyard sounds to use in the tracks Jerkins, his brother Fred, and songwriter LaShawn Daniels – who form the Darkchild production team – started the writing process.

But they were unsure of exactly how to write for Jackson, especially since he hadn’t been thrilled with the first batch of songs.

Cory Rooney recalls:

“Rodney called me and said, ‘Cory, we’re still confused. We don’t know what to write about. We don’t know what to do.”

At the time, Rooney had just written a song for Jackson called “She Was Loving Me,” which Jackson had flown to New York to record with Rooney at the Hit Factory.

Upon his return to LA, Rooney says that Jackson played the track for Jerkins and his team.

“Rodney said, ‘Cory… he loves your song. All he keeps playing for us is your song. What is it about your song that you think he loves? So I told him I got a little tip from Carole Bayer Sager. She told me that Michael is a storyteller. She said Michael loves to tell stories in his music. If you listen to Billie Jean, it’s a story. If you listen to Thriller, it’s a story. If you listen to Beat It, it’s a story. He loves to tell a tale.”

The Darkchild production team began working on music for Jackson at an LA studio called Record One, where other Jackson collaborators including Brad Buxer, Michael Prince and Dr. Freeze were already working on their own ideas for the pop star.

“Rodney was running his sessions like twenty-four hours per day,” remembers Prince.

“They even brought beds in to sleep on. When Rodney would get tired, he would go and lay down and Fred would come in and work on lyrics. When Fred would get tired, he’d go and wake up LaShawn, who would come in and work on some things.”

“Michael would call the studio at two or three o’clock in the morning to just check in and see what we were doing,” recalls Rodney’s brother, Fred Jerkins III.

“He was constantly motivating us to think beyond the scope of our normal imagination with these songs. It was incredible.”

“I used to sleep in the studio,” recalls Rodney.

“At every studio that I worked, I would make sure that they had a pull-out bed or something brought in for me because I would stay there for weeks at a time.”

Recording engineer Michael Prince recalls that the Darkchild production team worked so hard that the studio engineers couldn’t keep up:

“At some point, I remember the engineers coming to me and saying, ‘We can’t keep doing this. This is killing us!’ And I was like, just tell them. They’re people too! But they hung in there as long as they could.”

Producer Rodney Jerkins says that his work ethic was inspired by Jackson.

“He told me that if I was willing to really work hard, that we could make some magic together, and that’s what I did… I went in the studio and just really locked in and started creating nonstop every day.”

“We were in the studio for maybe a month before Mike came in, and we had all our ideas down. We had our melodies down, everything,” recalls Darkchild songwriter LaShawn Daniels.

“So when Mike finally came in, it was like the President coming in. The place was swept. Security came in, and it was going crazy.”

But it was Jackson’s knowledge of each member of the Darkchild production team that impressed Daniels the most:

“He came into the room and – surprisingly – he knew who each one of us was and what we did in respect to the project! Mike was so in tune with music as a whole that the stuff he told us still blows my mind.”

In a further attempt to point the Darkchild production team in the right direction when working on songs for Jackson, Cory Rooney suggested that they start simple:

“I told Rodney, let’s start with the rhythm. I said if you’re confused on the rhythm, just start with that four on the floor beat, because that never goes wrong. And just create your rhythms to counter the four on the floor.

With that advice in mind, the Jerkins brothers and LaShawn Daniels wrote a song that they believed was a hit.

“And that became the track for You Rock My World. And the rest is history because LaShawn Daniels and everybody dug in and wrote a story to it.”

Rodney Jerkins explains how “You Rock My World” came to be:

“Rock My World came about because I’m a fan of old Michael – like Off The Wall, Thriller, and The Jackson Five.”

Jerkins recalls that while Jackson was demanding new sounds, he felt it was also important to write songs that retained Jackson’s classic sound:

“Michael was like, ‘I want you to go outside and to take a bat and smash it against the side of a car and sample it.’ And I was doing it! He had me at junkyards with DAT recorders. And I was like, that’s all good, I’ll give you that, but you have to do this over here. And Rock My World was actually the first song that we wrote for Michael.”

By the time the demo to “You Rock My World” was ready for Jackson to hear, studio sessions had been shifted from Record One in Los Angeles to the Hit Factory and Sony Studios in New York City.

Rooney recalls that at that time, the Darkchild production team called him and invited him to come down to the studio to take a listen:

“They called me at the Hit Factory and said, ‘Cory, you’ve gotta come over. We think we’ve got it.’ When I walked in and they played me Rock My World, I almost passed out! I thought it was so amazing that I almost passed out. I was really, really blown away.”

Rooney recalls that he took the song to Jackson, so that he could hear the track:

“When I first played it for him he, asked me: ‘Do you love it?’ And I said yeah, yeah, I love it! And he said, ‘Well, I know you wouldn’t have come over here and played it for me if you didn’t like it, but do you love it?’ And I looked him right in his eyes and said Michael, I love it. I love this record. And he said, ‘Okay. I’ve got to be honest with you. I do like it. I don’t know if I love it yet, but I like it, and I’m going to just keep on living with it.’”

Rooney continues:

“If Michael is just a little bit interested in a song, you’re never gonna get him in the studio to record it. And so he lived with it, and showed up at the Sony studios in New York about a week later, with Rodney, and he kind of ran through the record.”

Darkchild songwriter LaShawn Daniels – who was an integral part of writing “You Rock My World” – remembers the moment Jackson came to the studio to work on the track.

“He had Rodney just play the track, and he said, ‘Who’s the guy doing the melodies?’ And it was me!”

Daniels continues:

“So I came into the room and Michael is standing there – freakin’ Michael Jackson! – and Mike comes up to me and says, ‘Rodney, play the track.’ And Rodney says, ‘Sure.’ Then Michael says to me, ‘Can you sing the melodies into my ear?’ And I’m like, are you serious? He’s like, ‘Just sing it in my ear.’ So I go right next to him, and I pull towards his ear, and I start singing.”

Daniels recalls that Jackson stopped him, and suggested they make minor change.

“He puts his hand on my shoulder and says, ‘No. Let’s change this part.’ And I’m like, oh, my god! When he asked me to do that, I was done. I couldn’t even continue, and I had to stop. I said, Mike, listen, I appreciate you being so cool, but you can’t be this cool with me. I don’t even know what to do right now. And I can’t concentrate on the melodies because I’m singing to Michael Jackson! And he burst out laughing and just made us comfortable.”

Former Sony executive Cory Rooney recalls that from there, Jackson had Jerkins repeat the track a few more times before recording a scratch vocal to see how he felt about it with his own voice on it.

“He played with it a little bit and sang the first few lines. And then he played it back, listened to it with his voice on it, and said, ‘Okay, now I love it! So let’s go to the top, and I’m gonna kill this record.’ And everybody was so relieved.”

Rooney recalls that Jackson loved the background vocals LaShawn Daniels had recorded, and he wanted to include them on the Darkchild tracks – something that Jackson had also done with songs he recorded with producer Dr. Freeze a year prior.

“Michael said: ‘Man, you’re killing it. I love it! Sounds great.’ He loved LaShawn Daniels’ background vocals so much that he left them on You Rock My World and other songs they worked on together. Michael did the main notes but he left LaShawn in the background.”

Once “You Rock My World” was completed, Jackson challenged his newfound collaborative team to create even greater material.

“Those times with Michael… he taught me to challenge myself,” recalls Daniels.

“When we came up with the Rock My World melodies and everything, it felt great. We knew that was the record. But he came back and he said, ‘Challenge yourself. I’m not saying that this is not it, but can you beat it? If you can beat it, you’ve only touched greatness even more!’”

To guarantee that their focus would be on his project – and his project only – Jackson reportedly paid Rodney Jerkins the Darkchild production team not to work with anyone but him.

“He told me he wanted me to camp out and work on his album,” recalls Jerkins.

“I was slated to do about seven or eight artists… and Michael said, ‘No, no, no. You have to really focus on my project. I need you to really focus on this.’ And I was like yeah, but I got bills to pay. And he said, ‘I’ll take care of those. Tell me what they’re gonna pay you and how many songs and I’ll take care of it.’ So I ended up not working with all those different artists and just focusing on Michael.”

As production on the album progressed, the Darkchild team returned to New Jersey to continue working on unique sounds for Jackson, crafting rhythmic tracks from their library of sampled sounds – including sounds from those initial junkyard recordings.

“The process of working with Michael Jackson was so intense because he pushed me to the limit creatively,” explains Jerkins.

“He loves to create in the same kind of way that I like to create,” Jackson says of Jerkins.

“I pushed Rodney. And pushed, and pushed, and pushed, and pushed him to create. To innovate more. To pioneer more. He’s a real musician. He’s a real musician and he’s very dedicated and he’s really loyal. He has perseverance. I don’t think I’ve seen perseverance like his in anyone. Because you can push him and push him and he doesn’t get angry.”

“Michael would call me at four o’clock in the morning and say, ‘Play me what you got,’” remembers Jerkins.

“I’m like, um, I’m about to go to sleep. But that’s how he was. He was so into the creative zone. On most of the stuff I did with him, the snares were made out of junkyard materials.”

One of the songs that sprouted from the 1999 Darkchild sessions in New Jersey sessions was “Xscape” – originally penned as “Escape” per an early ASCAP Repertory listing.

“Xscape was a record that I actually wrote the hook for myself,” recalls Fred Jerkins III, adding that he even sang the very first demo of the track:

“I don’t do any singing on songs at all. But on that one I actually had to sing the demo first, before it went to LaShawn to do the final demo version. So I actually had to get in the booth and sing it, and then the rest of the song was built around the hook idea.”

An early demo of “Xscape” was first shown to Jackson during a phone call with Rodney Jerkins.

When Jackson heard what they’d come up with, according to Jerkins, he went crazy:

“He was like, ‘That’s what I’m talking about! That’s what I’m talking about!’ It made him want to dance… Michael, he just loved to dance and would always tell me, ‘Make it funky.’ So musically I kept the promise and he kept the promise melodically, and we made up-tempo songs that made you wanna dance.”

As with Cory Rooney’s “She Was Loving Me” a few months earlier, Jackson was so in love with “Xscape” that he wanted to recording it immediately.

Instead of travelling to New Jersey – where the Darkchild production team was working – Rodney Jerkins had Jackson use a new recording technique designed by EDnet that allows engineers to capture high-quality audio through a phone line.

And so Jackson sang the background vocals – usually the first part of a song Jackson would record – down the phone while Rodney recorded them.

“From that point we would go in and do the complete demo version,” recalls Rodney’s brother, Fred Jerkins III.

“LaShawn was the one who would demo on all of the songs for Michael, and he did a good job of trying to imitate him. We would try and provide the best feel for Michael about how the song should be.”

When the demo was ready, producer Rodney Jerkins collaborated with Jackson on the lyrics before recording the lead vocals. Co-writer of the track, LaShawn Daniels, explains:

“What we did with Michael – because he was a great songwriter – is we had the tracks and we put the rhythm of the melodies down so when he came in he could hear the basic idea of what we wanted to do, but allow him to be a part of the creative process of lyrics and all that type of stuff.”

Allowing the hook to lead the way, the track’s lyrics became a defensive musical exposé in line with previously-released tracks like “Leave Me Alone” and “Scream” – about how the pop star’s privacy is rarely respected, and how details of his private life are often twisted or fabricated when reported on in the media.

As with all of his music, Jackson was intimately involved with every nuance of “Xscape”.

Over the course of two years, Jackson and Jerkins continued to tinker with the track, adding new sounds and samples while bringing it closer and closer to completion.

“I tell them to develop it, because I’ve got to go on to the next song, or the next thing,” explains Jackson of his collaborative relationship with producers and songwriters.

“They’ll come up with something, working with my] ideas, and they’ll get back to me, and I’ll tell them whether I like it or not. I have done that with pretty much everything that I have done. I am usually there for the concept. I usually cowrite all the pieces that I do.”

“That was our process,” explains Rodney Jerkins.

“That’s the way we worked. We just kept at it until it was ready. We just worked on ideas, added this and that to the mix. Michael was like, ‘Dig deeper! Where’s the sound that’s gonna make you want to listen to it over and over again?’”

Engineer Brian Vibberts recalls working with Jerkins on “Xscape” at Sony Music Studio in New York City during the summer of 1999.

Vibberts, who also worked on Jackson’s HIStory album in 1995 and music for his Ghosts film in 1996, claims that Jackson was physically present at the studio far less during the Invincible sessions when compared to previous projects.

“Rodney would send the song to Michael, then talk to him on the phone. Michael would give him input on the song and request the changes that he wanted made. Then we would do those changes.”

One of the changes that was made to the original Darkchild demo was the addition of a cinematic spoken intro.

“He called them vignettes,” says Rodney Jerkins. “I call them interludes.”

“It was a really fun process, working on that project,” adds Rodney’s brother, Fred.

“We would actually sit in the studio in LA and act out the whole Xscape concept, the intro, just acting crazy and making video footage and all that kind of stuff. Almost like our video concept of the song.”

Another interesting addition to “Xscape,” which Jackson brought to the table, is the Edward G. Robinson line from the 1931 film Little Caesar: “You want me? You’re going to have to come and get me!”

Fifteen years prior, the same line was lifted from the film and sampled in an unreleased version of Jackson’s demo for a song called “Al Capone,” as outlined in the Blue Gangsta chapter of my book Michael Jackson: Songs & Stories From The Vault.

In “Xscape,” however, Jackson himself speaks the famous line, shortening it to: “Want me? Come and get me!” ‘

Of the decision to include the Little Caesar line, producer Rodney Jerkins says: “It was MJ’s idea.”

By the middle of the year 2000, the Jackson’s new album seemed to be nearing completion.

Since he started working on it in 1998, Jackson had recorded more than a dozen tracks including “She Was Loving Me,” “You Rock My World,” “Xscape” and “We’ve Had Enough” – the latter of which spawned from the early 1999 writing session Jerkins attended at Carole Bayer Sager’s home in LA.

With enough tracks in the bag to finish the album, the mixing process began.

To assist Jackson’s team with mixing the album, producer Rodney Jerkins brought an engineer named Stuart Brawley on board.

“Michael’s longtime engineer of many years, Bruce Swedien, was looking for someone to come on board to help mix what we all thought at that time was a complete record,” recalls Brawley.

“It was supposed to be a month-long mixing process in Los Angeles and I just jumped at the opportunity to be able to work with both Michael and Bruce.”

But what was supposed to be just one month of mixing ended up being much more.

“It turned into a thirteen-month project because as we were mixing the record that we thought was going to become Invincible, Michael decided, in the mixing process, that he wanted to start writing all new songs,” recalls Brawley.

“He was like, ‘Let’s start from scratch… I think we can beat everything we did,’” recalls Rodney Jerkins of Jackson’s decision to start afresh by writing new songs.

“That was his perfectionist side. I was like man, we have been working for a year, are we going to scrap everything? But it showed how hard he goes.”

“It just turned into an amazing year of watching him create music,” recalls engineer Stuart Brawley. “We ended up with a completely different record at the end of it.”

While some of the early material – including “You Rock My World” – would ultimately make the cut, the majority of what became the Invincible album was recorded between 2000 and 2001.

During this period, the Jerkins brothers and LaShawn Daniels continued working on new songs, while Jackson’s longtime producer Teddy Riley also joined the team.

At the time, Riley was working out of a studio that was built inside a bus.

Upon joining the project, Riley would park his bus outside whichever studio Jackson was working in, and and the pop star would bounce back and forth between Riley and Rodney Jerkins.

Meanwhile, arranger Brad Buxer and engineer Michael Prince worked out of makeshift studios set up in local hotel rooms.

Towards the end of the project, Riley moved his sessions to Virginia – where he had a recording studio – to finish the tracks he was working on.

Recording engineer Stuart Brawley – who was instrumental in recording and editing some of the newer songs, like “Threatened” – recalls what it was like to work with Jackson:

“It was amazing just to have him on the other side of the glass when we were recording his vocals. It literally was that ‘pinch me’ moment, and I don’t get those. He was just one of a kind. There was no one else like him.”

“Being in the studio and just having the a cappella of Michael’s vocals and listening to them, you start to really understand how great he really was,” explains Rodney Jerkins of Jackson’s performance on “Xscape.”

“The way he crafted his backgrounds, the approach of his lead vocals, and how passionate he was. You can hear it. You can hear his foot [stomping] in the booth when he’s singing, and his fingers snapping.”

During the second phase of the Invincible album’s production – between 2000 and 2001 – Jackson and Jerkins continued to work on “Xscape.”

“Wait until the world hears Xscape,” Jerkins recalls Jackson saying to him.

“MJ loved everything about it. The energy, the lyrics. It’s kind of a prophetic song. Listen to the bridge. MJ says, ‘When I go, this problem world won’t bother me no more.’ It’s powerful.”

“The thing about Michael is he will work on a song for years,” adds Jerkins.

“We never stopped working on the song Xscape.”

“A perfectionist has to take his time,” explains Jackson.

“He shapes and he molds and he sculpts that thing until it’s perfect. He can’t let it go before he’s satisfied; he can’t… If it’s not right, you throw it away and you do it over. You work that thing till it’s just right. When it’s as perfect as you can make it, you put it out there. Really, you’ve got to get it to where it’s just right; that’s the secret. That’s the difference between a number thirty record and a number one record that stays at number one for weeks. It’s got to be good. If it is, it stays up there and the whole world wonders when it’s going to come down.”

Jackson continues:

“I’ve had musicians who really get angry with me because I’ll make them do something literally several hundred to a thousand times till it’s what I want it to be,” says Jackson. “But then afterwards, they call me back on the phone and they’ll apologise and say, ‘You were absolutely right. I’ve never played better. I’ve [never] done better work. I outdid myself.’ And I say, ‘That’s the way it should be, because you’ve immortalised yourself. This is here forever. It’s a time capsule.’ It’s like Michelangelo’s work. It’s like the Sistine Chapel. It’s here forever. Everything we do should be that way.”

After three years of work, the Invincible album was released on October 30, 2001.

The album contained 16 songs. But to the surprise of some who worked on the project, “Xscape” was not one of them.

“There’s stuff we didn’t put on the album that I wish was on the album,” explains Jerkins, whose unreleased material includes “Get Your Weight Off Me” and “We’ve Had Enough” – the latter of which was later released by Sony on a box set called The Ultimate Collection in 2004.

A number of tracks Jackson recorded with Brad Buxer and Michael Prince also missed the cut, including “The Way You Love Me,” which was also released on The Ultimate Collection box set.

Several tracks Jackson worked on with producer Teddy Riley did make the cut. But one, called “Shout,” did not.

“Shout” was slated to be on the album, but was replaced at the last minute by a track Jacksons’s manager, John McClain, brought brought to the table called “You Are My Life” – co-written by McClain with Kenneth ‘Babyface’ Edmonds and Carole Bayer Sager.

“I really want people to hear some of the stuff we did together which never made the cut,” laments producer Rodney Jerkins.

“There’s a whole lot of stuff just as good – maybe better [than what made the album]. People have got to hear it.”

Despite it not being included, Jackson continued working on “Xscape” with Jerkins.

The producer explains that selecting the tracks for an album isn’t always about which tracks are best in isolation, but which tracks fit together to create a cohesive and organic flow:

“Michael is like no other. He records hundreds… really, hundreds of songs for an album. So what we did [was] we cut it down to 35 of the best tracks and picked from there. [It’s] not always about picking the hottest tracks. It’s got to have flow. So there’s a good album’s worth of [unreleased] material that could blow your mind. I really hope this stuff comes out because it’s some of his best.”

Engineer Michael Prince recalls a conversation he had with fellow engineer Stuart Brawley about the unreleased track “Xscape” after the Invincible album had been released.

“I was talking to Stuart Brawley on the phone… And I said to Stuart, this song is awesome! And he goes, ‘I know. It’s an amazing song. I really, really wish they would have put that on the album and took something else off. I told Rodney, I told Michael, but they’re not putting it on the album.’ And after I heard it I felt the same way. I really like the song Xscape.”

“I had a conversation with MJ in 2008, and I asked him if he was a fan of the British act Scritti Politti,” adds Prince.

“He said he was. I asked him that because the original version of Xscape has some of the same type of short staccato sounds and sampled percussive sounds that Scritti Politti use in their music. They also used very inventive sequencing, as Michael and Rodney Jerkins did on Xscape.”

“When we originally did Xscape, Mike felt it was some of his best new music,” recalls Rodney Jerkins.

“So I asked him, Michael, how come Xscape is not going on Invincible? And Michael was like, ‘Nah… I don’t want it on this project. I want it on the next project.’ Michael was very clear in telling me that one day that song has to come out… It was one of his favourite songs… It was one of those songs where he specifically said to me, ‘It has to see the light of day one day’… He felt compelled to let the fans hear it. What does it do for a song that Michael really loved to just sit in the vault somewhere?”

And eventually Jackson’s fans did hear it – but not in the way he or Jerkins had hoped.

In late 2002, “Xscape” leaked online.

“The reality is that you get upset when something gets out there that’s not supposed to be out there,” explains Fred Jerkins of his feelings about the leak.

“You want it to come out the way it should, and to give it the best possible chance of doing what it needs to do. But at the same time, as a fan – if you step aside from the songwriter side – you’re excited that you have something out there. And you watch other people get excited.”

Reflecting on their work with Jackson on “Xscape” – and the Invincible project as a whole – the thing that sticks with Darkchild teammates Rodney Jerkins and LaShawn Daniels more than anything is his desire to be great.

“Michael embodied greatness in everything that he did,” says Jerkins.

“Not just as an artist, but as a humanitarian and as a person. That was his life. He was all about being great and he preached it all the time.”

Since he was a teenager, Jackson’s artistic philosophy has been to ‘study the greats and become greater,’ and for the duration of his four-decade career, that pursuit of greatness never faded.

“Michael would be in the lounge watching footage on Jackie Wilson, James Brown and Charlie Chaplin,” recalls Jerkins.